Abstract

Almost everyone struggles to act in their individual and collective best interests, particularly when doing so requires forgoing a more immediately enjoyable alternative. Other than exhorting decision makers to “do the right thing,” what can policymakers do to reduce overeating, undersaving, procrastination, and other self-defeating behaviors that feel good now but generate larger delayed costs? In this review, we synthesize contemporary research on approaches to reducing failures of self-control. We distinguish between self-deployed and other-deployed strategies and, in addition, between situational and cognitive intervention targets. Collectively, the evidence from both psychological science and economics recommends psychologically informed policies for reducing failures of self-control.

Men are rather reasoning than reasonable animals for the most part governed by the impulse of passion.

—Alexander Hamilton (1802)

1. Self-control failures contribute to a range of policy issues, from educational achievement (Duckworth et al., in press) and retirement savings (Benartzi & Thaler, 2013) to the obesity epidemic (VanEpps et al., 2016a) and the promotion of subjective well-being (Wiese et al., 2018). People with greater self-control fare better in terms of health, wealth, and many other dimensions of human flourishing (Moffitt et al., 2011). Scholarly attention to self-control has grown dramati- cally over the past 2 decades, as shown in Figure 1, which depicts the percentage of articles about self- control in Psychological Science from 1995 through 2016. But inquiry on this timely topic stretches back thousands of years (Aristotle, trans. 2009; Freud, 1916/1977; James, 1899; Proverbs 25:28; Smith, 1759/1976; Thaler & Shefrin, 1981).

2. Why is self-control an object of fascination for phi- losophers, social scientists, policymakers, and pundits alike? Perhaps because failures of self-control often persist even when people recognize them and resolve to act differently in the future (Norcross & Vangarelli, 1988–1989). From forgoing dessert to exercising regu- larly to saving for retirement, many people feel as if they are in a perennial battle with themselves. Further- more, most people predict incorrectly that they will overcome this battle (e.g., Augenblick & Rabin, 2018), even when they recognize that other people’s self- control problems persist (Fedyk, 2017; Pronin, Lin, & Ross, 2002). Finally, temptations—rewards that provide short-term gratification but impede people from long- term goals—are ever more abundant, thanks to conve- nience stores, one-click shopping, social media, 24/7 streaming video, and other new vices (Akst, 2011).

3. Not all decisions require self-control. Sometimes deci- sions are difficult because people feel torn between two equally valuable choices (Shenhav & Buckner, 2014). In addition, self-control is irrelevant when people are simply mistaken about the actual costs and benefits of their choices. In the 1940s, for example, smoking cigarettes was not widely perceived as an unhealthy habit; indeed, tobacco companies then touted the health benefits of smoking. The carcinogenic effects of cigarette smoking are now common knowledge, and 68% of smokers in the United States would like to quit smoking (Babb, 2017).

4. The special case of self-control conflict entails a ten- sion between want and should: A “should” behavior (e.g., exercising, eating healthy, going to bed early) is more valuable in the long-run, whereas an alternative “want” behavior (e.g., staying on the couch, eating junk food, staying up late) is more alluring in the moment (Milkman, Rogers, & Bazerman, 2008). When people pursue the option with more enduring value, they expe- rience self-control success; when they pursue the option that is more tempting right now, they experience self-control failure.

5. Three classes of models in economics and psycho- logical science endeavor to explain when and why self-control conflicts arise. Here we provide a short summary of these three models. For a detailed com- parison and contrast of leading intertemporal-choice models, as well as a review of the relevant empirical evidence, see Cohen, Ericson, Laibson, and White (2016) and Ericson and Laibson (2019).

6. The first class of models features multiple sequential selves with dynamically inconsistent preferences1 (e.g., Ainslie, 2012). Each self exists at a point in time, and each self wants instant gratification followed by a future life characterized by patient behavior, a good work ethic, and the willingness to delay gratification when it is beneficial. According to this approach, decision makers exhibit dynamic inconsistency in their choices insofar as the future tends to be sharply discounted relative to the present. This produces a peculiar pattern whereby choices about the future emphasize patience (e.g., “Next Tuesday, I want to have salad for lunch!”), but choices made for the present prioritize immediate gratification (e.g., “Right now, I want a cheeseburger!”). Although the decision makers always know what they want to do in the moment, these current preferences contradict their own past plans (Ainslie & Haslam, 1992; Akerlof, 1991; Laibson, 1997; Loewenstein & Prelec, 1992; O’Donoghue & Rabin, 1999). Models in this class tend to use hyperbolic or quasihyperbolic discount functions. Hyperbolic functions tend to be a special case of the general functional form for discount func- tions proposed by Loewenstein and Prelec (1992), in which events at horizon are discounted (i.e., weighted) with the function: (1 + αt)−γ/α. Here the parameters α and γ are both positive. The quasihyperbolic (or “present- biased”) model of Laibson (1997) tries to reproduce many of the properties of a hyperbolic discount func- tion in a way that is more tractable for mathematical modelling. The present-biased model gives current util- ity flows full weight and discounts future utility flows with the function β × δt. Here both parameters are weakly bounded between 0 and 1. The present “bias” is captured by the parameterization β < 1. When β = 1, the model reproduces the special case of pure exponential discount- ing, in which preferences are dynamically consistent: That is, early selves and later selves all agree on the best course of action (so there is no self-control problem).

7. The second class of models posits multiple coexist- ing selves. This view holds that decision makers behave as if they were a composite of competing selves with different valuation systems and different priorities. One “self” craves instant gratification (e.g., “I want to eat a cheeseburger! Yum!”), whereas another “self” is focused on maximizing long-term outcomes (e.g., “I want to eat a salad and be healthy!”). Self-control conflicts are the consequence of a present-oriented valuation system disagreeing with a future-oriented valuation system (Fudenberg & Levine, 2006; Loewenstein & O’Donoghue, 2004; Thaler & Shefrin, 1981). In a typical implementa- tion of this framework (e.g., Fudenberg & Levine, 2006), there are two types of selves that play a repeated game: a patient (dynamically consistent) long-run self, which might discount payoffs exponentially, and a sequence of completely myopic short-run selves that care only about immediate payoffs. Thaler and Shefrin (1981) call these selves the “planner” and the “doer,” respectively. Evidence for multiple system models comes from func- tional MRI (fMRI) studies showing that self-controlled choices were associated with lateral prefrontal areas of the brain, whereas more impulsive choices were associ- ated with the ventral striatum and ventromedial pre- frontal cortex (e.g., Figner et al., 2010; McClure, Ericson, Laibson, Loewenstein, & Cohen, 2007; McClure, Laibson, Loewenstein, & Cohen, 2004).

8. A third class of multiple-attribute models suggests that although the phenomenology of self-control con- flicts may suggest a duality—an effortful struggle between present and future selves or between multiple coexisting selves—there is nothing fundamentally dif- ferent between such conflicts and any other kind of choice (Berkman, Hutcherson, Livingston, Kahn, & Inzlicht, 2017). Instead, attributes of the choices among which people must select are presumed to be hetero- geneous, including hedonic reward value, effort costs, the costs and benefits of social signaling, and more. For example, a cheeseburger may be appraised as high in hedonic value but low in long-term-health value. A salad, in contrast, may be lower in hedonic value but higher in long-term-health value. Rather than warring systems of preferences, this view of self-control conflict posits multiple streams of information, each of which represents different attributes of people’s choices. Neurobiological evidence favoring the multiple-attribute model includes fMRI studies in which areas of the brain previously considered part of a present-oriented decision-making system (e.g., ventral striatum) were associated with both delayed and immediate rewards (Kable & Glimcher, 2007).

9. Regardless of their underlying mechanics, self- control conflicts are an everyday challenge, and peo- ple’s failures to act in their long-term interest are commonplace. Why? Succeeding at self-control requires people to do more than decide to forego what they want in order to do what they should. As Mischel (2007) recognized at the beginning of his career, intention and action are not always identical: “After the choice to delay has been made, the good intention formed and declared at least to oneself, what allows it to be real- ized?” (p. 265). In the preschool delay-of-gratification paradigm that Mischel later developed, children are offered a smaller treat (e.g., one marshmallow) right away or a larger treat (e.g., two marshmallows) if they can wait. Although nearly all children decide to wait for a larger, later treat rather than enjoy a smaller treat right away, how long children can follow through on this resolution varies dramatically (Duckworth, Tsukayama, & Kirby, 2013; Mischel, Shoda, & Rodriguez, 1989).

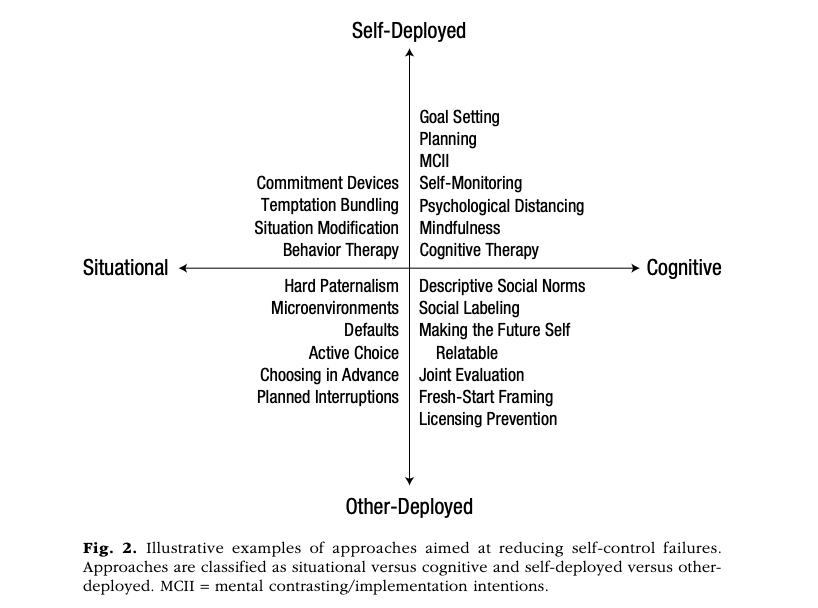

10. In this review, we provide a theoretical framework for organizing the myriad strategies that have been shown empirically to reduce self-control failures. We argue for the distinction between situational and cogni- tive strategies, as well as the distinction between strate- gies deployed by the individual (i.e., self-initiated self-control strategies) and those deployed by third- parties (i.e., nudges initiated by policymakers, employ- ers, etc.). We summarize policy-relevant intervention research in both psychological science and economics with the goal of inspiring research-supported policies and programs for decreasing failures of self-control. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of the relative advantages and disadvantages of each approach.

Strategic Interventions to Reduce Failures of Self-Control

11. From early childhood, human beings have some capac- ity to directly suppress one urge in favor of a goal- congruent rival urge (Eisenberg, Smith, & Spinrad, 2011), a feature of the behavioral repertoire that relies on executive function and is supported by the most recently evolved areas of the human brain (Cohen, 2005; McClure et al., 2004). The vernacular term will- power is used to describe this straightforward, brute- force approach to doing what is in one’s best interest when an alluring alternative beckons (Mahoney & Thoresen, 1972). Though the capacity to directly modu- late impulses continues to improve throughout adoles- cence and early adulthood (De Luca et al., 2003), self-control failures are common at any age (Baumeister, Heatherton, & Tice, 1994).

12. Likewise, public policies that prescribe internal for- titude for resisting immediate gratification tend to dis- appoint. Consider, for example, the “Just Say No” campaign, inspired by then First Lady Nancy Reagan’s three-word response to a schoolgirl who asked what she should do if someone offered her drugs. The sub- sequent Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) pro- gram implemented by a majority of U.S. school districts in the 1980s has been shown in some studies to have had unintended negative effects (Werch & Owen, 2002) and in meta-analyses to have had no measurable benefit for youth alcohol, drug, and tobacco use (West & O’Neal, 2004).

13. We propose a classification of approaches that takes more strategic aim at failures of self-control. As shown in Figure 2, our classification distinguishes between approaches that modify one’s situation and approaches that modify one’s cognitions, depending on whether they target the objective situation or, in contrast, one’s mental representation of the environment. The phe- nomenology of resisting temptation—typically experi- enced as effortful, tiring, and unpleasant (Hagger, Wood, Stiff, & Chatzisarantis, 2010; Inzlicht, Bartholow, & Hirsh, 2015; Inzlicht, Schmeichel, & Macrae, 2014; Kurzban, Duckworth, Kable, & Myers, 2013)—naturally directs our attention to cognitive strategies for solving this problem. However, situational strategies can be especially efficient insofar as they can be executed long before impulses have grown strong enough to be noticed (Duckworth, Gendler, & Gross, 2016).

14. Figure 2 further differentiates between strategies that are self-deployed and those that are other-deployed. In the former, individuals take deliberate action to improve their decisions; in the latter, individuals may be oblivi- ous to the actions that other parties initiate on their behalf. Self-deployed strategies require some amount of “sophistication,” or conscious awareness of the pos- sibility of future self-control conflicts (Laibson, 1997; Strotz, 1955). For example, although weekly cognitive or behavior therapy relies on the skills and attention of a therapist, it nonetheless requires the client’s coop- eration and consent. In contrast, rearranging a cafeteria so that healthy options are within easy reach requires neither. A similar distinction—between self-deployed “boosts” and other-deployed “nudges”—has been made by Hertwig and Grüne-Yanoff (2017). The crucial dif- ference is self-awareness: To be effective, a boost requires recognizing one’s self-control problem, but a nudge does not.

15. Note that self-awareness about self-control can be unreliable. On Monday, people may valiantly battle their impulses to overeat, but on Wednesday, they may deny, even to themselves, the need to reign in their diet, only to begin the cycle anew the following week. Likewise, on the timescale of months or years, it is common for addicts to cycle in and out of conscious awareness of their problems (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992). Although metacognitive awareness surely varies, not only across time but also among decision makers (O’Donoghue & Rabin, 1999), we are concerned in this review with any behavior with which many (but not necessarily all) decision makers struggle (but not always in earnest) to act in their best interest, despite momen- tary temptations that lead them to act otherwise.

16. Like any framework, our 2 × 2 classification simplifies at the expense of nuance. What makes categorization so tricky? One reason is that situational interventions often influence decision making via cognitive mecha- nisms (Duckworth, Gendler, & Gross, 2016). For instance, turning your phone off to resist wasting time on social media is a self-deployed situational strategy that in turn encourages you to ignore, or even forget about, what your friends may be posting online. Relat- edly, a cognitive intervention such as self-monitoring (i.e., paying attention to healthy versus unhealthy behavior) can be facilitated by a situational affordance such as a food journal or pedometer.

17. Furthermore, the distinction between self-deployed and other-deployed interventions reflects how these approaches are typically implemented. It is possible that a strategy that we have categorized as self-deployed could be other-deployed and vice versa. A teenager, for example, might independently decide to turn off the phone, or his or her parent might encourage him or her to do so. Conversely, if you listen to a podcast about the benefits of tackling behavior change at moments that feel like a “fresh start” (Dai, Milkman, & Riis, 2014), you may take it on yourself to begin a new exercise program on your birthday, but your employer may make use of the same information to advertise gym discounts on New Year’s Day. And, finally, real-world interventions are very often a concatenation of diverse elements representing distinct categories of strategies. Weight Watchers, for example, coaches dieters to use an array of self-deployed situational and cognitive strat- egies and, in addition, sponsors in-person meetings, communicates social norms, and provides a phone app to track eating and exercise.

18. Despite these complexities, a classification of strate- gies aimed at reducing self-control failures illuminates commonalities and distinctions among approaches developed in diverse theoretical traditions. For exam- ple, the adjacency in Figure 2 of commitment devices and hard paternalism reveals a through line: Both are situational interventions that change the objective costs and benefits of self-controlled versus impulsive choices. At the same time, their placement in separate quadrants is also revealing: Commitment devices are self-deployed, requiring the individual’s self-awareness of future fal- libility, whereas hard paternalism is other-deployed and in many cases is justified by lack of self-awareness on the part of individual decision makers.

Empirical Research on Interventions That Reduce Failures of Self-Control

19. Beginning in the top-left quadrant of Figure 2 and then proceeding clockwise, we describe interventions designed to decrease self-control failures. With an eye toward policy recommendations, our review emphasizes interventions that have been tested in field settings. However, we also identify a few promising interventions for which empirical support derives primarily from labo- ratory research. Using the same metric as the original publications, we include effect sizes for field-tested interventions and, where available, meta-analytic esti- mates. By convention, many of the publications we review use the terminology “small,” “medium,” and “large” to refer to mean differences (d) of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 SD, respectively (Cohen, 1992). For analysis-of- variance models, η2 is often reported, in which case the corresponding effect-size conventions are .01, .06, and .14, respectively (Richardson, 2011). When numeric effect-size estimates are unavailable but authors describe effects as “small,” “medium,” or “large,” we follow suit, noting recent critiques that these rules of thumb are both arbitrary and unrealistic, particularly with respect to behavioral outcomes in real-world settings (Bosco, Aguinis, Singh, Field, & Pierce, 2015; Hill, Bloom, Black, & Lipsey, 2008; Kraft, 2018). Wherever relevant, we high- light contradictory results and competing perspectives.

20. It is beyond the scope of this review to identify and critique the methodological limitations of each study that we reference. We urge the reader to proceed with two general cautionary comments in mind. First, almost all of the experiments reviewed here were published before contemporary concerns about reproducibility in social science research. We believe more precise and accurate estimates of effect sizes for diverse interven- tion approaches will emerge once norms and proce- dures are established for preregistration, reporting of null effects, multiple attempts at replication, and a priori power analyses (which generally call for larger samples than typical in the published literature; see Shrout & Rodgers, 2018). Second, we restrict our review to published studies. Consider as context a metasyn- thesis of 62 separate meta-analyses of interventions for change in health behaviors such as smoking and physi- cal activity (B. T. Johnson, Scott-Sheldon, & Carey, 2010). When 100% of studies for meta-analyses came from scientific journals (as opposed to being unpub- lished), the estimated effect of interventions (d) was 0.26, but when only 45% of studies were published in journals, the average effect of interventions was 0.01.

Self-deployed interventions