Chapter 21 The Math of Success

For example, after Dilbert became a hit, I briefly considered launching a second comic. I posted on the original Dilbert website some early samples of what I hoped would be a comic about a young Elbonian boy who didn't fit in. His name was Plop, and he was the only unbearded Elbonian in the world, and that included the women and babies. On day one, the Plop comic was a lot better than the first Dilbert comics, but not nearly as good as Dilbert had become by that time. What I didn't count on—my blind spot—was that my new comic would be compared to Dilbert, not to other new comics. Compared to Dilbert, it was flat and lacked an edge. Compared to all the new comics that launched that same year from unknown cartoonists, it was fairly competitive. Most of my feedback by email was of the "Keep your day job" variety along with "It's no Dilbert." I wouldn't have guessed that being a successful cartoonist would be a barrier to launching a new comic, but in my case it was. I could have saved a lot of time if I understood that in advance.

For example, after Dilbert became a hit, I briefly considered launching a second comic. I posted on the original Dilbert website some early samples of what I hoped would be a comic about a young Elbonian boy who didn't fit in. His name was Plop, and he was the only unbearded Elbonian in the world, and that included the women and babies. On day one, the Plop comic was a lot better than the first Dilbert comics, but not nearly as good as Dilbert had become by that time. What I didn't count on—my blind spot—was that my new comic would be compared to Dilbert, not to other new comics. Compared to Dilbert, it was flat and lacked an edge. Compared to all the new comics that launched that same year from unknown cartoonists, it was fairly competitive. Most of my feedback by email was of the "Keep your day job" variety along with "It's no Dilbert." I wouldn't have guessed that being a successful cartoonist would be a barrier to launching a new comic, but in my case it was. I could have saved a lot of time if I understood that in advance.

Dilbert was the first syndicated comic that focused primarily on the workplace. At the time, there was nothing to compare it to. That allowed me to get away with bad artwork and immature writing until I could improve my skills to the not-so-embarrassing level. Since the launch of Dilbert in 1989, dozens of cartoonists have tried to enter the workplace-comic space and got clobbered by unfavorable comparisons to a mature Dilbert. If I were to disguise my identity and launch a new workplace comic tomorrow, with all new characters, readers would compare it to Dilbert, and it wouldn't stand a chance.

For the past twenty years or so, I have been in a few dozen meetings on the topic of turning Dilbert into a feature film. I always get the question of how we could make a Dilbert movie different enough from the TV show The Office or the cult movie Office Space. The implication is that the quality of a Dilbert movie might be less important to its success than whatever the public reflexively compares it to. Quality is not an independent force in the universe; it depends on what you choose as your frame of reference.

When my restaurant partner and I built our second restaurant, we decided to make it more upscale than the first so it wouldn't cannibalize business, given that the two restaurants were only five miles away. The upscale décor strategy seemed like a perfectly good idea until I observed women walk in for lunch, look at the upscale décor, look at their own casual clothes, and proclaim to the hostess that they were underdressed. The self-assessed underdressed customer would turn and leave. I saw that scenario repeat itself over and over. None of the women who rejected themselves from the restaurant looked underdressed to me. The restaurant wasn't that upscale. It was still a neighborhood restaurant in a suburban strip mall. But compared to other restaurants in the area, it was a step up in design. It made people feel uncomfortable. To make matters worse, our food quality wasn't up to the level people expected for a place with that type of décor. The restaurant's appearance caused us to be compared to the very best of fine dining restaurants. Our business model assumed people would prefer eating upscale comfort food in an unusually attractive setting. It was a bad idea. Customers were confused. Was the restaurant supposed to be casual or upscale? People compared our décor to casual restaurants and decided it was too fancy to be a casual eating experience. They compared our food to the top restaurants in San Francisco and decided it wasn't sufficiently special. We failed to predict how customers would stack us up against alternatives.

This book itself presents an especially challenging comparison problem. If I add too much humor to this book, reviewers and readers will compare it to other humor books, and it will come up short because many of the chapters don't lend themselves to jokes. If I leave out all humor, the book will be compared to self-help books, which would be misleading in its own way, but I'd probably come out better in that sort of comparison. In other words, to increase your perceived enjoyment of the book, I might leave out some humor that you would otherwise enjoy.

When I talk of the comparison problem, I don't mean a simple comparison of one thing to its competition. If the competition is simply better than you, your problem is more than customer perception. I'm talking about comparisons that common sense tells you should be irrelevant, such as comparing Dilbert the TV show to The Simpsons. They weren't competitors in any real way. They didn't run during the same slot or exhaust the limited supply of the public's discretionary time in any meaningful way. And yet the comparison to The Simpsons was a big obstacle to the show's success because it contrasted a seasoned, big-budget show against a poorly-funded upstart that was still trying to find its rhythm. Animated shows take longer to "tune" than live action because the writers for animation can't know what worked in a particular show until it is fully animated and too late to change. Success in anything usually means doing more of what works and less of what doesn't. For animated TV shows, that means you don't hit your pace until about the third season. We got cancelled after the second half-season. I believe that if The Simpsons had never existed as the gold standard of animated primetime TV shows, the Dilbert show would have had time to reach the next level.

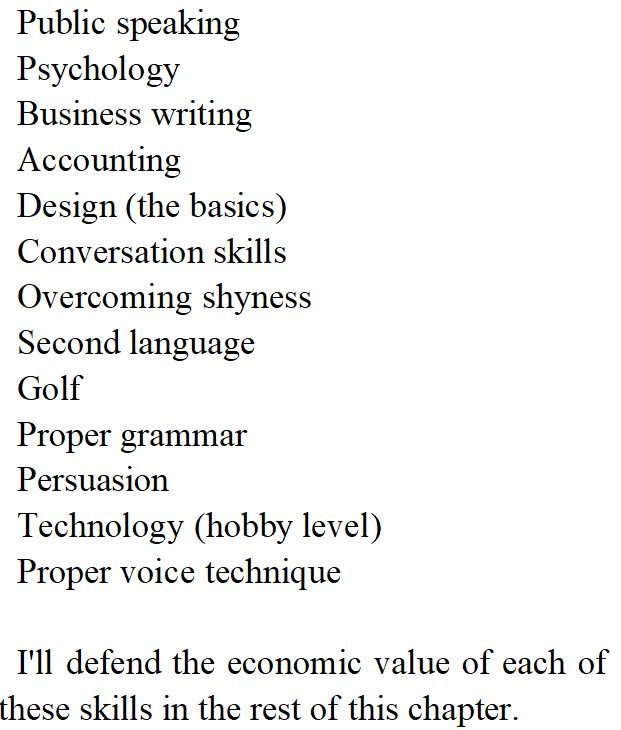

I've spent a lot of time describing just one psychological phenomenon: the tendency to make irrational comparisons. But how many psychological tips and tricks does a person really need to understand to be successful in life?

My best guess is that there are a few hundred rules in psychology you should have a passing familiarity with. I've been absorbing information in this field for decades, and I don't feel as if I'm getting anywhere near the end of it. And just about everything I learn about human psychology ends up being helpful.

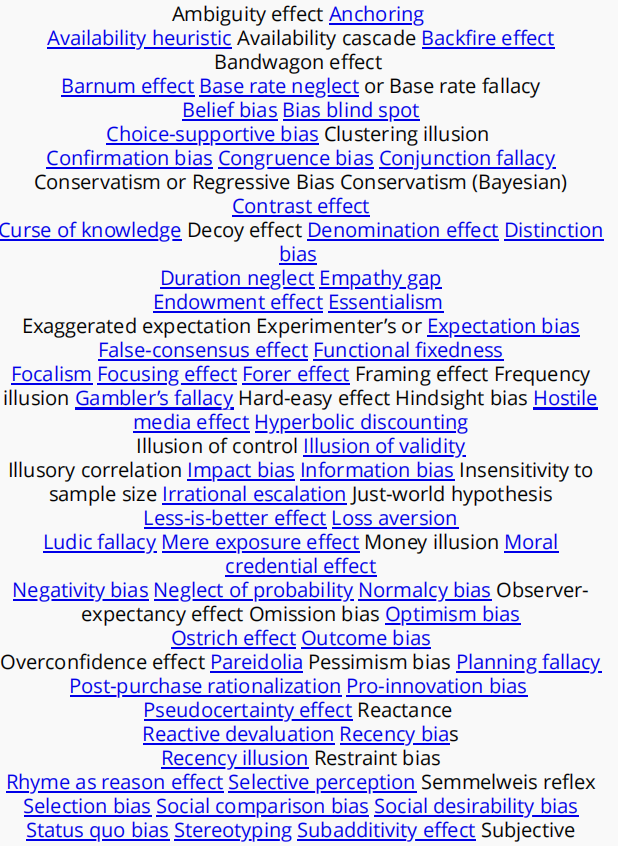

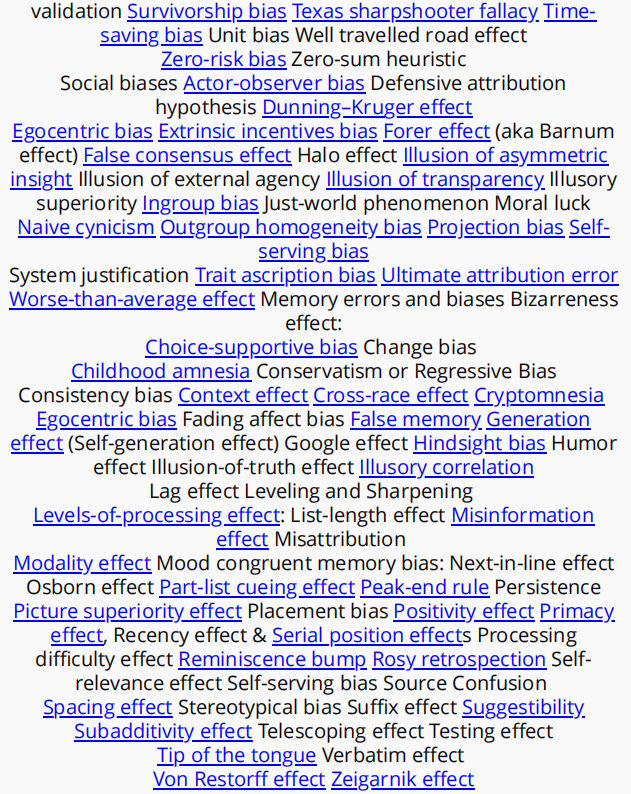

I went to Wikipedia to get a quick list of the psychological and cognitive traps that humans often fall into. Psychology is an immense field and well beyond the scope of this book. My point is to impress upon you how many useful nuggets of information are at your disposal, and most of them are free. Every psychological trap on this list can be used to manipulate you. If there's something on this list that you're not familiar with, you're vulnerable to deception. In some cases, you're missing opportunities to make your product and yourself more attractive to others.

It's a good idea to make psychology your lifelong study. Most of what you need to know as a regular citizen can be gleaned from the Internet.

Below is Wikipedia's list of cognitive biases.1 It looks like a lot to know, but you have your entire life to acquire the knowledge. Think of it as a system in which you learn a bit every year. That will be easier if you understand how important psychology is to everything you want to accomplish in life. On a scale of one to ten, the importance of understanding psychology is a solid ten.

Some entries on the list are common sense, and you might already know them by other names. I include the comprehensive list just to give you a feel for how deep the field is. And I would go so far as to say that anything on the list you don't understand might cost you money in the future.

You've heard the old saying that knowledge is power. But knowledge of psychology is the purest form of that power. No matter what you're doing, or how well you're doing it, you can benefit from a deeper understanding of how the mind interprets its world using only the clues that somehow find a way into your brain through the holes in your skull.

When I was in my twenties, I took a certification course in hypnosis. I thought it would be fascinating and maybe useful. I even considered making some money on the side as a hypnotist. I decided against it because I didn't want to be in the business of selling my time. But the skills and insights I gleaned from studying hypnosis have improved my performance in just about everything I've done since then, from business to my personal life. It was time well spent.

In hypnosis, you don't spend much time asking why one technique works and why another does not. Hypnosis is largely a trial-and-error process that uses your own experience plus that of hypnotists who have gone before to reduce the number of wrong moves. In that sense, hypnosis treats people as if they are machines that can be programmed. If you provide the right inputs, you get the outputs you want.

Hypnosis is an inexact process because every brain has a different mix of chemistry. For example, if I ask you to relax and imagine a forest in the summer, you might find that a pleasing image. Unless you are afraid of bears or are scared of getting lost in the wilderness, then you might get agitated by the thought of a forest. A hypnotist learns to detect slight changes in breathing, posture, movement, and skin tone to know if the images presented are working as planned. Adjustments are made accordingly. In the simplest terms, a hypnotist tries to do more of whatever works and less of what doesn't.

My experience with hypnosis completely changed the way I view people and how I interpret the choices they make. I no longer see reason as the driver of behavior. I see simple cause and effect, similar to the way machines operate. If you believe people use reason for important decisions, you will go through life feeling confused and frustrated that others seem to have bad reasoning skills. The reality is that reason is just one of the drivers of our decisions, often the smallest one.

Recently, my wife and I went shopping for a new vehicle. We looked at a lot of models online and in person, and none were irresistible. Then we came upon a vehicle that was so "us" that I laughed when I saw it. I could almost feel my brain make up its mind before we had done one iota of reasoning, data gathering, or negotiating. I could tell that my wife had the same experience. This car was so obviously going to belong to us that seeing it was like peering into the future.

Predictably, everything we learned about the car after that point seemed either good or good enough. We convinced ourselves that the price was reasonable. We convinced ourselves that the features were just what we wanted. And eventually, we convinced ourselves we had negotiated a good deal.

The normal way people would look at our car-buying experience is that we saw a model that looked good enough to interest us, then we did our homework, applied our reasoning abilities, and came to a rational decision. The reality is quite different. The amateur hypnotist in me knows that our visceral reaction to the car was the beginning and end of the "thinking" that went into the purchase. We did some due diligence to make sure it met our basic requirements, yes, but we already "knew" it would. The purchase was an irrational decision that tried and failed to sell itself to me as the product of reason.

It is tremendously useful to know when people are using reason and when they are rationalizing the irrational. You're wasting your time if you try to make someone see reason when reason is not influencing the decision. If you've ever had a frustrating political debate with a friend who refuses to see the logic in your argument, you know what I mean. But keep in mind that the friend sees you exactly the same way.

When politicians lie, they know the press will call them out. They also know it doesn't matter. Politicians understand that reason will never have much of an effect on voting decisions. A lie that makes a voter feel good is more effective than a hundred rational arguments. That's even true when the voter knows the lie is a lie. If you're perplexed at how society can tolerate politicians who lie so blatantly, you're thinking of people as rational beings. That worldview is frustrating and limiting. People who study hypnosis start to view humans as moist machines that are simply responding to inputs with programmed outputs. No reasoning is involved beyond eliminating the most absurd options. Your reasoning can prevent you from voting for a total imbecile, but it won't stop you from supporting a halfwit with a great haircut.

If your view of the world is that people use reason for their important decisions, you are setting yourself up for a life of frustration and confusion. You'll find yourself continuously debating people and never winning except in your own mind. Few things are as destructive and limiting as a worldview that assumes people are mostly rational.

On an episode of The Bachelorette, a show on ABC, one of the contending single men played a practical joke on the young woman he hoped to marry. The joke involved taking her to his parents' home and convincing her that he still lived there, which he didn't. The joke was well-executed, complete with a fake bedroom that was a disgusting mess. What the suitor failed to understand is that the bachelorette would still feel the scenario in the joke long after the truth was revealed. In the bachelorette's mind—the irrational part we all have—the memory of this fellow being a live-at-home loser was like a stain that couldn't be removed. I think the bachelorette genuinely appreciated the joke and had a good laugh. But my wife and I turned to each other and said, "He's toast." He was eliminated soon after. We can't know how much impact the joke had on the bachelorette's decision, but my training with hypnosis tells me it was probably huge.

Apple owes much of its success to Steve Jobs' understanding that the way a product makes users feel trumps most other considerations, including price. If Steve Jobs saw people as rational beings, he might have followed a path similar to Dell, selling highly capable machines at the lowest possible price. Dell succeeded, too, of course, but if buyers were rational, there would have been only one computer manufacturer left after about a year; consumers would always buy the best computer for the money and drive out the bad players overnight. Luckily for Dell and several other Windows computer manufacturers, there are enough irrational people with poor information to keep several companies afloat so long as their products are confusingly similar. Jobs' worldview led him to a business model with high margins, whereas Windows computers have become commodities.

If you feel I'm overstating the case that people are irrational, allow me to put some boundaries around that idea. People certainly make small decisions based on rational considerations. You probably invest your money in ways that are prudent—or so you think. But keep in mind that the financial meltdown of 2009 happened because even the best investors were irrationally optimistic about financial instruments they couldn't hope to understand.

Rational behavior is especially useless in any situation that is too complex for a human to grasp. Cellphone companies exploit that fact by offering pricing plans too complicated to compare to the competition. (I coined the word "confusopoly" to describe that strategy.) The intent is to prevent consumers from using whatever small reasoning power they possess to compare prices and features. Instead, consumers make largely uninformed decisions and convince themselves they did well. I speak from experience, having recently moved from one wireless carrier to another while planning a third move soon. I tell myself that each of the moves was based on price, coverage, and features. But reason didn't help me the first two times I chose a wireless carrier, and it probably won't help the next time because the pricing plans are intentionally hard to compare.

I don't think you need to become a hypnotist to understand human psychology, although it helps. But I do think a working knowledge of psychology is essential to your success—both personally and professionally. Consider it a lifelong learning process. You'll be glad you undertook it. Over time, knowing the psychology basics starts to feel like a superpower that allows you to understand what confuses and confounds those around you.

Business Writing

I never took a writing class in high school or in college. I learned the basics in English classes, and those seemed good enough. I could write sentences that people understood. What else did I need?

I did notice that some people in the business world wrote with an impressive level of clarity and persuasiveness. But I figured that was just because those people were extra smart. It never occurred to me that there was some technique involved and that we unwashed citizens could easily learn it.

One day during my corporate career, I signed up for a company-sponsored class in business writing. This was part of my larger strategy of learning as much as I could about whatever might someday be useful while my employer was willing to foot the bill. I didn't have high hopes that the class would change my life. I was just looking for some tips and tricks for better writing.

I was very wrong about how useful the class would be. If I recall, the class was only two afternoons long. And it was life-altering.

As it turns out, business writing is all about getting to the point and leaving out all the noise. You think you already do that in your writing, but you probably don't.

Consider the previous sentence. I intentionally embedded some noise. Did you catch it? The sentence that starts with "You think you already do that ..." includes the unnecessary word "already." Remove it, and you get the same meaning: "You think you do that ..." The "already" part is assumed and unnecessary. That sort of realization is the foundation of business writing.

Business writing also teaches that brains are wired to better understand concepts that are presented in a certain order. For example, your brain processes "The boy hit the ball" more easily than "The ball was hit by the boy." In editor's jargon, the first sentence is direct writing and the second is passive. It's a tiny difference, but over the course of an entire document, passive writing adds up and causes reader fatigue.

Eventually, I learned that the so-called persuasive writers were doing little more than using ordinary business writing methods. Clean writing makes a writer seem smarter and makes their arguments more persuasive.

Business writing is also the foundation for humor writing. Unnecessary words and passive writing kill the timing of humor the same way they kill the persuasiveness of your point. If you want people to see you as smart, persuasive, and funny, consider taking a two-day class in business writing. There aren't many skills you can learn in two days that will serve you this well.

Accounting

I found accounting nearly impossible to learn because of the bubbling moat of boredom that surrounds the entire field. But a basic understanding of accounting is necessary to be a fully effective adult in a modern society, even if you never do any actual accounting on your own.

Accounting is part of the vocabulary of business, and if you don't understand it on a concept level, the world will be a confusing place. In particular, it's helpful to be able to create your own cash flow projection on a spreadsheet and feel some confidence that you understand the tax impact and the so-called time value of money.†† Accounting overlaps with the fields of economics and business, and in each of those fields, you need to understand accounting practices.

In my town there's a tiny restaurant that has changed hands several times, always with a new concept and menu. The one thing that all the concepts have in common is that they can't work because there aren't enough tables in the place to cover their expenses. (I have a good idea what their expenses are because I once owned two restaurants in the area.) My guess is that the new operator has plenty of culinary expertise but no accounting knowhow. No one with accounting skill would get involved with a business model that can't work on paper.

You can pay others to do your accounting and cash flow projections, but that only works if you can check their work in a meaningful way. The smarter play is to learn enough about accounting and spreadsheets that you understand the basics.

Design

In today's world, we're all designers whether we like it or not. You might be designing PowerPoint presentations, a website for your startup, or flyers for your kid's school event. You're also furnishing your home, buying clothes you hope look nice to others, and so on. Design used to be the exclusive domain of artists and other experts. Now we're all expected to have a working understanding of design.

If you're like me, you were born with no design skills whatsoever. I was amazed to learn, well into my adult years, that design is rules-based. One need not have an "eye" for design; knowing the rules is good enough for civilians.

For example, landscape designers will tell you that it's better to put three of the same kind of bush in your yard, not two and not four. Odd numbers just look better in that context. You don't need an eye for design to count to three, and you get the same result as the expert, at least in that limited example.

I also learned that art composition for anything from a magazine cover to an oil painting to a PowerPoint slide should conform to a few basic templates. The most common is the L-shaped layout. You imagine a giant letter L on the page and fill in the dense stuff along its shape, leaving less clutter in one of the four open quadrants. Artists call the uncluttered part negative space. In the case of an oil painting, you might have a tree going up one side, some landscape on the bottom, and the open sky in the top left. You can change it up by rotating the L and leaving a different quadrant less busy than the rest, but it's still the L concept.

When you take a photograph, you can use the same concept. Instead of centering the person in the pictures, adjust your field until the person is one side of the L and the ground is the bottom. The less busy quadrant might be some landscape or the sunset.

When you design a PowerPoint slide or a web page, it's the same idea. You leave one quadrant less busy than the rest. Skim through any well-designed magazine and you'll see the L design in 80 percent of the art and photography. The other 20 percent will be some special cases that I won't go into here. I'm only trying to convince you of the importance of design and the ease with which you can pick up the main idea. Learn just a few design tricks, and people will think you're smarter without knowing exactly why.

Conversation Skills

Few people are skilled conversationalists. Most people are just talking, which is not the same thing. The difference is that skilled conversationalists have learned techniques that are surprisingly non-obvious to a lot of people. I was among the clueless about conversation skills for the first half of my life. When I was a teen, I thought conversation was a complete waste of time and something to be avoided. I was aware that there were several alleged reasons for conversation, but I didn't see much value in them. I was a bore.

There are probably a dozen or more reasons to have a conversation, depending on how you slice it. You might start a conversation to ...

Exchange information

Plan

Complain