Leading with Intentionality: The 4P Framework for Strategic Leadership

Copyright 2020 Wilkinson, Robert; Leary, Kimberlyn; and the President and Fellows of Harvard College at Harvard University Center for International Development

Introduction

The year 2020 has brought one crisis after another, perhaps exacerbating a common belief that a “heroic leader” can save the day. But does this mythical figure really exist? Leadership, once we study it, isn't one thing exercised at the top by one person, as our colleague and leadership expert Ron Heifetz has observed; it is an activity exerted by people at all levels, and by noticing certain less obvious aspects of leadership, anyone can improve at it.

Leadership is possible any time there is a collective problem. Each of us may have a role to play in mobilizing others to address community problems, and each of can improve our skills to be more effective. In truth, the ability to exercise leadership effectively requires skills and capacities that must be developed; they are not innate.

Leadership is rarely making one decision and sticking to it, or making a grand development happen with a touch. Mostly, leadership is non-heroic and involves painstaking work, paying attention, and being able to learn quickly and in real time. Over the last twenty-five years, we have been privileged to lead organizations and public initiatives, consult to global organizations, and teach public policy graduate students and senior executives.

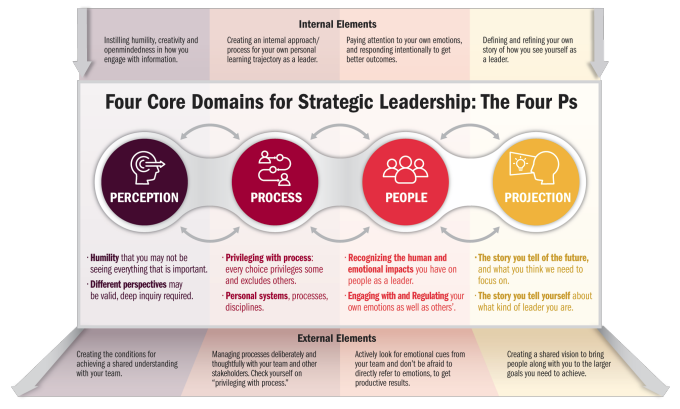

This experience enabled us to identify four key elements that seem to improve the odds of leadership success—what we call “four Ps”: perception, process, people, and projection. In our classrooms, often through the use of case studies, we teach leadership stories of successes as well as failures or ambiguous situations where the leader experienced an unexpected outcome.

Over time, we have found that advancing organizations or movements relies on activities that include these “four Ps.” As an example, about fifteen years ago, Tarana Burke led an empowerment workshop for young Black girls in Tuskegee, Alabama. Much of the discussion had been about sexual assault and at the end of the workshop the girls were invited to either write down three things they had learned, or, if they had survived sexual violence they could just write “Me, too.”

Not wanting them to feel singled out for revealing their trauma, Burke still hoped to offer them a space to begin healing. At the end of the meeting the organizers were flooded with sheets of paper that said “Me, too.” This was a decade before two New York Times journalists published an exposé on the movie producer Harvey Weinstein that most people think kicked off the “Me, too” movement.

Burke is now a national figure, but there was no one moment when she became a leader. Years of inspiring girls in small community settings to see themselves as valuable and agents of their own future meant she was leading all along. Fear of false accusations against Black men and concerns for family privacy meant that many in her community were instinctively wary of focusing attention on sexual violence against girls, so Burke juggled matters of perception.

Her process was inclusive and sequential, understanding that empowerment couldn't happen without first addressing survivors' trauma. Fundamental to her approach was a skilled use of empathy and an understanding of the power of emotion in human beings—the people component—that meant meeting participants where they were, addressing the shame survivors carried with them, and assuring them that they were not alone.

Finally came her projection—the way she told a story. Burke turned the narrative of sexual abuse from being victim-based to survivor-based, so girls and women who had endured sexual violence could tap into their inherent power and move forward. A “Four P” Framework Leadership involves intentional work. It is not necessarily about charisma or a powerful personality unleashed.

It involves a great deal of reflection, challenging the self, and respect for others. Each of the Ps outlined here draws from existing literature and incorporates multiple academic and practitioner frameworks. And leadership always remains an approach; a way of engaging problems and working with people.

It is a constant learning journey that requires practice, deliberation, repetition, and growth over time. Each of these “four Ps” has an internal and external component, so we are, in fact, studying eight domains of leadership. “Internal” refers to the work needed to do on one’s own and “external” to the way we engage with others.

With perception, you expose and examine your own assumptions. With process, yours matters as much as the team’s—how you manage your regular routines, habits and individual reflection. With people, your emotions and your understanding of them matter as much as those of others. With projection, you are thinking of your own story as much as the group’s—the story you tell yourself about who you are in the world about what you see around you.

Perception

We've all had the experience of attending the same meeting, listening to the same speech, or watching the same movie only to discover that our colleagues or family members saw something different. Our default assumption is that everyone sees it the same way we do, and we tend to push forward in that conviction.

Leadership requires the discipline to slow down and think about multiple perspectives before acting; a discipline that requires inquiry and curiosity. In the summer of 2020, the Memorial Day killing of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers prompted widespread protests against racial inequality and aggressive policing, and a reckoning with racist symbols including Confederate statues and monuments.

In many cities, protesters demanded that statues be torn down, and many were. Five years before, when a young white supremacist murdered nine Black parishioners at a church in Charleston, South Carolina, similar protests arose but without 2020’s momentum.

Christopher Columbus was targeted, too: In New Haven, Connecticut, and Boston’s North End—where many elderly Italian-Americans remembered the prejudice against their families—Columbus was an Italian-born explorer to be proud of, not someone who brought genocide to North America as many young protesters of color claimed.

Clearly, people were not going to agree. But could they empathize? The inevitable human tendency to see things a certain way and not consider how differently others might see it is a perennial test of leadership. On a team, it can be confused with disloyalty: “I thought we were on the same page,” someone might say, as if the mere fact of disagreeing signals that you are not part of the team.

Similarly, “We are all part of the same team,” often means, “If you don’t agree with me, you aren’t being a team player.” A common response when confronting an opposing view is to think agreement is demanded as the only way forward: “You're telling me that I have to agree with or accept what the other side is saying, which is anathema to everything I stand for.”

But perception is not about reaching agreement, it's another proposition: Before you reach your conclusion, you have work to do, to try to deeply understand and be curious enough to inquire before you know how to proceed.

- Literature:

Psychologists have studied our inclination to see the world as we want to see it and our tendency to dismiss information that contradicts our default positions. “Naïve realism,” as described by R.J. Robinson, means we assume everyone sees the world the same way, because in front of our eyes we believe there is just an objective reality.

We assume a “false consensus” that others naturally share our views. Furthermore, our opponents who don't share our understanding are irrational or biased.3 All three judgments are dangerous in leadership. They suggest skipping from “here is where we are” to “here is where we are going” and leaping to the end of the story where everyone on the team has bought in. But the skipped steps can derail the project, wasting time and money.

- What you can do:

Moving past the perception block requires a willingness to ask questions and an openness to enter into difficult conversations; it’s a deliberate process that is the opposite of avoidance or a heedless path where the leader blindly carries on doing things her or his way.

In Difficult Conversations, Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, and Sheila Heen came up with three questions: First, what did the other person actually say or do? Second, what impact did they, in fact, have on me? Third, what assumptions did I make about why they did what they did?

Did I separate the fact of what they said from what I assumed about it—my assumptions being, perhaps, that they were untrustworthy, incompetent, or some other value judgment? Because inevitably we began to tell a story—if only in our head—about this person reflecting our larger world view. And the separation grows.

-Internal Perception:

In 2017, when an earlier wave of protests erupted over Confederate statues, Mayor Jim Gray of Lexington, Kentucky, had the authority to remove two of the monuments from outside the county courthouse. He made the decision not to, but renewed pressure from a coalition of Lexington community groups forced him to reconsider.