多人英文轮本,该系列Part 3,选自《纽约时报》Modern Love专栏英文故事,同名美剧(豆瓣8.8分)取材。

5个bgm分别对应5个故事,配合bgm效果更佳。

目录

1. When Cupid Is a Prying Journalist

2. The Secret to Marriage Is Never Getting Married

3. DJ’s Homeless Mommy

4. My Unlikely Pandemic Dream Partner

5. Hear That Wedding March Often Enough, You Fall in Step

(禁止转载,如有侵权,请联系作者处理)

1. When Cupid Is a Prying Journalist

By Deborah Copaken

My interview with Justin McLeod was winding down when I tossed out one last question: “Have you ever been in love?”

The baby-faced chief executive had designed Hinge, which was a new dating app. My question was an obvious throwaway.

Justin looked stricken. No one, he said, had ever asked him that in an interview. “Yes,” he finally answered. “But I didn’t realize it until it was too late.” Then he asked me to turn off my recorder. I hit Stop.

Off the record, he looked relieved to unburden himself. Her name was Kate. They were college sweethearts. He kept breaking her heart. (Tears now swelled in his eyes.) He wasn’t the best version of himself back then. He had since made amends to everyone, including Kate. But she was now living abroad, engaged to someone else.

“Does she know you still love her?” I asked.

“No,” he said. “She’s been engaged for two years now.”

“Two years?” I said. “Why?”

“I don’t know.”

I was by then a year into a separation from a two-decade marriage. I had been doing a lot of thinking about the nature of love, its rarity. The reason I was interviewing Justin, in fact, was that his app had helped facilitate a post-separation blind date, my first ever, with an artist for whom I had fallen at first sight.

That had never happened to me, the at-first-sight part. He was also the first man to pop up on my screen after I downloaded Justin’s app.

For those keeping score at home, those are a lot of firsts: first dating app, first man on my screen, first blind date, first love at first sight. I was interested in understanding the app’s algorithm, how it had come about, how it had guessed, by virtue of our shared Facebook friends, that this particular man, a sculptor with a focus on the nexus between libidinal imagery and blossoms, would take root in my heart.

“You have to tell her,” I said to Justin. “Listen —— ” and I told him the story of the boy I had loved just before meeting my husband.

He was a senior in college, studying Shakespeare abroad. I was a 22-year-old war photographer based in Paris. We had met on a beach in the Caribbean, then I visited him in London, shell-shocked, after having covered the end of the Soviet-Afghan war.

I thought of him every day I was covering that war. When I was sleeping in caves, so sick from dysentery and an infected shrapnel wound on my hand that I had to be transported out of the Hindu Kush by Doctors Without Borders, my love for him is what kept me going.

But a few weeks after my trip to London, he stood me up. He said he would visit me at my apartment in Paris one weekend and never showed. Or so I thought.

Two decades later, I learned that he actually had flown to Paris that weekend but had lost the piece of paper with my address and phone number. I was unlisted. He had no answering machine. We had no friends in common. He wound up staying in a hostel, and I wound up marrying and having three children with the next man I dated. And so life goes.

By the time Google was invented, the first photo of me to appear on his screen was of my children and me from an article someone had written about my first book, a memoir of my years as a war photographer. Soon after, he married and had three children with the next woman he dated. And so life goes.

I found him by accident, doing research on theater companies for my last novel. There he was above his too-common name. I composed the email: “Are you the same man who stood me up in Paris?”

That’s how I learned what had happened that weekend and began to digest the full impact of our missed connection.

His work brought him to New York a few months later, and we met for a springtime lunch on a bench in Central Park. I was so flummoxed, I kicked over my lemonade and dropped my egg salad sandwich: Our long-lost love was still there.

In fact, the closure provided by our reunion and the shock of recognition of a still-extant love that had been deprived of sun and water would thereafter affect both of our marriages, albeit in different ways. He realized how much he needed to work on tending to his marriage. I realized I had given mine all the nutrients and care I could — 23 years of tilling that soil — but the field was fallow.

Hearing of Justin’s love for Kate while seated on another New York City bench four years later, I felt a fresh urgency. “If you still love her,” I told him, “and she’s not yet married, you have to tell her. Now. You don’t want to wake up in 20 years and regret your silence. But you can’t do it by email or Facebook. You actually have to show up in person and be willing to have the door slammed in your face.”

He laughed wistfully: “I can’t do that. It’s too late.”

Three months later, he emailed an invitation to lunch. The article I wrote about him and his company, in which he had allowed me to mention Kate (whom I had called his “Rosebud”), had generated interest in his app, and he wanted to thank me.

On the appointed day, I showed up at the restaurant and found the hostess. “Justin McLeod, table for two,” I said.

“No,” he said, suddenly behind me. “For three.”

“Three? Who’s joining us?”

“She is,” he said, pointing to a wisp of a woman rushing past the restaurant’s window, a blur of pink coat, her strawberry blond hair trailing behind her.

“What the —— ? Is that Rosebud?”

“Yes.”

Kate burst in and embraced me in a hug. Up close she resembled another Kate — Hepburn, who had appeared in the comedies of remarriage I had studied in college with Stanley Cavell.

These films, precursors to today’s rom-coms, were made in America in the 1930s and ’40s, when showing adultery or illicit sex wasn’t allowed. To pass the censors, the plots were the same: A married couple divorced, flirted with others, then remarried. The lesson? Sometimes you have to lose love to refind it, and a return to the green world is the key to reblossoming.

“This is all because of you,” Kate said, crying. “Thank you.”

Now Justin and I were tearing up, too, to the point where the other diners were staring at us, confused.

After we sat down, they told me the story of their reunion, finishing each other’s sentences as if they had been married for years. One day, after a chance run-in with a friend of Kate’s, Justin texted Kate to arrange a phone conversation, then booked a trans-Atlantic flight to see her without warning. He called her from his hotel room, asked if he could stop by. She was to be married in a month, but three days later, she moved out of the apartment she had been sharing with her fiancé.

I felt a pang of guilt. The poor man!

It was O.K., she said. Their relationship had been troubled for years. She had been trying to figure out a way to postpone or cancel the wedding, but the invitations had already been sent, the hall and caterer booked, and she didn’t know how to resolve her ambivalence without disappointing everyone.

Justin had arrived at her door at nearly the last moment he could have spoken up or forever held his peace. By the time of our lunch, the two were already living together.

Soon afterward, I had them over for dinner to introduce them to the blossom-obsessed artist who bore half of the responsibility for their reunion. He and I hadn’t worked out as a couple, much to my pain and chagrin, but we had found our way back into a close friendship and even an artistic collaboration after he texted me a doodle he’d been drawing.

In fact, we had just signed a contract to produce three books together: “The ABC’s of Adulthood,” “The ABC’s of Parenthood” and — oh, the irony — “The ABC’s of Love.”

“What was the doodle?” Kate asked.

I showed her the drawing on my iPhone.

“Are those ovaries?” she asked, smiling.

“Or seeds,” I said. “Or flower buds, depending on how you look at it.”

All perfectly reasonable interpretations of love begetting love begetting love, which is why we were all gathered around my table that night, weren’t we? Because real love, once blossomed, never disappears. It may get lost with a piece of paper, or transform into art, books or children, or trigger another couple’s union while failing to cement your own.

But it’s always there, lying in wait for a ray of sun, pushing through thawing soil, insisting upon its rightful existence in our hearts and on earth.

2. The Secret to Marriage Is Never Getting Married

By Gabrielle Zevin

I am often asked if I am married. Sometimes I lie and say that I am. Sometimes I lie and say that I am not. Neither answer feels entirely truthful to me.

If I say I am not married, the true answer, people occasionally try to set me up with their offspring. They seem to think I would be a great daughter-in-law. Actually, I would be a great daughter-in-law. I send thank-you cards. I am a terrific conversationalist. I can bake a pie.

I met the man I am not married to the second week of college.

“You’re wearing black,” Hans said. “I’m wearing black.”

This was said with some irony; we were standing in a black box theater. Everyone was wearing black. He had a girlfriend, so we didn’t get together until several months later. We have been together ever since, 21 years.

A year before I met Hans, a relative of his opened a credit card in his name and charged the better portion of another relative’s wedding. And then she forgot to pay the bill. For years. Forever, actually.

Hans didn’t find out until two years after the crime, when he was applying to graduate school. Even after making arrangements to pay off the debt, his credit was ruined and he couldn’t get student loans. The credit card company told him the only way to clear his credit would be to take the relative to court. Identity theft is a serious crime, the company said, and she could possibly go to jail.

Hans wouldn’t do it because the woman had a child, and he didn’t want the child to grow up without a mother. I liked that about him. He was in his early 20s and less than poor. But what difference did it make? He was a person of integrity, and we were in love. We had been together six months.

It can be awkward to describe this situation to people I don’t know. They tend to ask follow-up questions: “Why didn’t you just clear the credit cards and then get married?”

“Why didn’t I?” I say lightly.

The answer is: many reasons. Because I was 18 when I met him and didn’t know how long the relationship would last. Because it was a lot of money and I was embarrassed to ask my parents for help. Because neither of us had regular jobs and we both wanted to be artists more than we wanted to be married people. Because one of us needed good credit in order to rent apartments and charge groceries. Because by the time we had the means to make honest people of ourselves, we felt as if we had been together too long to bother.

But I don’t say any of these things.

“Don’t you like weddings?” someone will ask.

I love weddings. The odd mix of religion, government and pageantry moves me. It’s like theater, but with real people.

I have been to weddings. I have seen the white dresses. I have worn the bridesmaid dress. I have smelled the roses. I have never caught the bouquet, but I have watched its trajectory with enthusiasm. I have heard the wedding band play “Shout,” and I have gotten a little bit louder now.

I have shopped the registries, and I have sent the pasta makers, the towels, the knives and the vases. I am comfortable with the fact that as a person who has no plans to marry, I will not receive the pasta maker, the towel, the knives or the vase in return.

Hans and I have been together a long time, and for better or for worse, we have those things already.

My accountant recently broached the subject of marriage with me. He has been my accountant for the last 13 years, and I feel as if he’s my second most important long-term relationship. We were discussing whether I should consider getting married now.

I said, “It feels like it has been too long.”

I guess because I am turning 40 this year, he said, “Well, there are reasons to be married when you are old.” The reasons fell largely into two categories: What happens when I die? And what happens if I get sick and then die?

Once, on the way back from Japan, a customs agent was furious at Hans and me for sharing a checked suitcase when we weren’t related. We were not family, which meant we needed to speak to customs separately. So how to deal with the problem of a shared suitcase? What was a customs agent to do?

“Well, you see,” I remember saying, “when he was in college, a relative opened up this credit card, and...”

Basically, this encounter encapsulated the reason to get married at this peaceful midpoint of our lives. Because as you get old, per my accountant, life becomes a series of skirmishes with customs agents.

I know he is right. At this point, though, the math bothers me. I don’t want to start over again at Year 1. I worry that if Hans and I were to get married now, it would somehow be like saying the last two decades didn’t count.

I have had four dogs with the man I am not married to. I have dedicated several of my books to him, but really, they all could be. He is my most important reader and creative collaborator. We have traveled the world with one suitcase. We have cooked more than 100 Blue Apron meals without killing each other. We have shared a dozen different addresses. We have built a life. But we are not married. We live in California, which means we are not even common-law married.

Some time ago — we had not been married for 15 years — when we had an apartment by Riverside Park in New York, Hans woke up, looked out the window and said with boyish, almost biblical conviction, “Everything is telling me that’s Kristen Schaal.”

She was on one of our favorite shows, “The Flight of the Conchords.” We went down to walk our dog and the woman was still sitting in the park.

It was not Kristen Schaal. It could not have been less Kristen Schaal. And now we say this to each other all the time: “Everything is telling me that’s Kristen Schaal.” It is amazing how often this can be worked into conversation. This won’t be funny to anyone but the man I am not married to.

Our friends recently got divorced. They had been together as long as we had, and I had thought they were happy. But you can never know what goes on between two people. I asked her, “What percentage of time would you say you were happy?”

“Twenty percent,” she said. Several weeks later, she revised her estimate: “Maybe 2 percent.”

“Two!” I said. “How can a person live in a state of 2 percent happiness?”

“Perhaps 3,” she revised again.

Hans and I are happy together most of the time. We have the usual domestic squabbles. Our most frequent argument ends with him throwing up his hands and saying, “I’m not a handyman!”

Sometimes I think the secret to a long and happy marriage is never to get married in the first place, although there are surely married couples that are as happy as we are.

Not long ago, when a woman asked me the marriage question, I stumbled on what I believed to be the correct answer: “I have been with the same man for more than two decades, but I am not sure either of us believes in marriage.” I felt clever for stating my situation so concisely.

“Belief,” she scoffed. “Belief is for little children and Santa Claus.”

She was right. It’s just words to say I don’t believe in marriage. Having stayed with a person for more than 20 years, I must believe in marriage. I must believe that life is better in a pair than it is single.

When I say I don’t believe in marriage, what I mean to say is: I understand the financial and legal benefits, but I don’t believe the government or a church or a department store registry can change the way I already feel and behave.

Or maybe it would. Because when the law doesn’t bind you as a couple, you have to choose each other every day. And maybe the act of choosing changes a relationship for the better. But successfully married people must know this already.

I wake up in the morning and I look at Hans and think, I love you. I choose you above any other person. I chose you 21 years ago and I choose you today. I believe you to be a constant in my life, and I, a constant in yours. Loving you is the closest thing I have to faith. Everything is telling me that’s Kristen Schaal.

3. DJ’s Homeless Mommy

By Dan Savage

There was no guarantee that doing an open adoption would get us a baby any faster than doing a closed or foreign adoption. In fact, our agency warned us that, as a gay male couple, we might be in for a long wait. This point was driven home when both birth mothers who spoke at the two-day open adoption seminar we were required to attend said that finding “good, Christian homes” for their babies was their first concern.

But we decided to go ahead and try to do an open adoption anyway. If we became parents, we wanted our child’s biological parents to be a part of his life.

As it turns out we didn’t have to wait long. A few weeks after our paperwork was done, we got a call from the agency. A 19-year-old homeless street kid — homeless by choice and seven months pregnant by accident — had selected us from the agency’s pool of screened parent wannabes. The day we met her the agency suggested all three of us go out for lunch — well, four of us if you count Wish, her German shepherd, five if you count the baby she was carrying.

We were bursting with touchy-feely questions, but she was wary, only interested in the facts: she knew who the father was but not where he was, and she couldn’t bring up her baby on the streets by herself. That left adoption. And she was willing to jump through the agency’s hoops — which included weekly counseling sessions and a few meetings with us — because she wanted to do an open adoption, too.

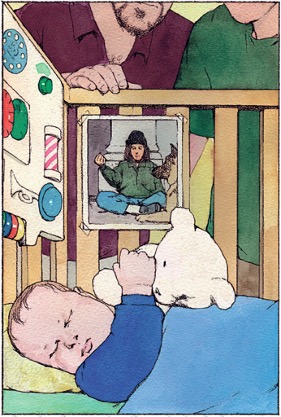

We were with her when DJ was born. And we were in her hospital room two days later when it was time for her to give him up. Before we could take DJ home we literally had to take him from his mother’s arms as she sat sobbing in her bed.

I was 33 when we adopted DJ, and I thought I knew what a broken heart looked like, how it felt, but I didn’t know anything. You know what a broken heart looks like? Like a sobbing teenager handing over a two-day-old infant she can’t take care of to a couple she hopes can.

Ask a couple hoping to adopt what they want most in the world, and they’ll tell you there’s only one thing on earth they want: a healthy baby. But many couples want something more. They want their child’s biological parents to disappear so there will never be any question about who their child’s “real” parents are. The biological parents showing up on their doorstep, lawyers in tow, demanding their kid back is the nightmare of all adoptive parents, endlessly discussed in adoption chat rooms and during adoption seminars.

But it seemed to us that all adopted kids eventually want to know why they were adopted, and sooner or later they start asking questions. “Didn’t they love me?” “Why did they throw me away?” In cases of closed adoptions there’s not a lot the adoptive parents can say. Fact is, they don’t know the answers. We did.

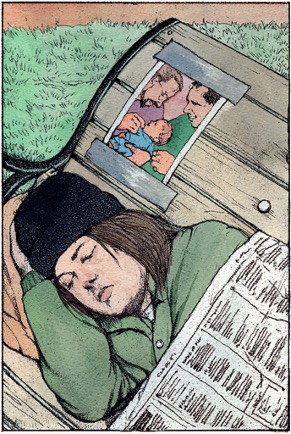

Like most homeless street kids, our son’s mother works a national circuit. Portland or Seattle in the summer. Denver, Minneapolis, Chicago and New York in the late summer and early fall. Phoenix, Las Vegas or Los Angeles in the winter and spring. Then she hitchhikes or rides the rails back up to Portland, where she’s from, and starts all over again.

For the first few years after we adopted DJ his mother made a point of coming up to Seattle during the summer so we could get together. When she wasn’t in Seattle she kept in touch by phone. Her calls were usually short. She would ask how we were, we’d ask her the same, then we’d put DJ on the phone. She didn’t gush. He didn’t know what to say. But it was important to DJ that his mother called.

When DJ was 3, his mother stopped calling regularly and visiting. When she did call, it was usually with disturbing news. One time her boyfriend died of alcohol poisoning. They were sleeping on a sidewalk in New Orleans, and when she woke up he was dead. Another time she called after her next boyfriend started using heroin again. Soon the calls stopped, and we began to worry about whether she was alive or dead. After six months with no contact I started calling hospitals. Then morgues.

When DJ’s fourth birthday came and went without a call, I was convinced that something had happened to her on the road or in a train yard somewhere. She had to be dead.

I was tearing down the wallpaper in an extra bedroom one night shortly after DJ turned 4. His best friend, a boy named Haven, had spent the night, and after Haven’s mother picked him up, DJ dragged a chair into the room and watched as I pulled wallpaper down in strips.

“Haven has a mommy,” he suddenly said, “and I have a mommy.”

“That’s right,” I responded.

He went on: “I came out of my mommy’s tummy. I play with my mommy in the park.” Then he looked at me and asked, “When will I see my mommy again?”

“This summer,” I said, hoping it wasn’t a lie. It was April, and we hadn’t heard from DJ’s mother since September. “We’ll see her in the park, just like last summer.”

We didn’t see her in the summer. Or in the fall or spring. I wasn’t sure what to tell DJ. We knew that she hadn’t thrown him away and that she loved him. We also knew that she wasn’t calling and could be dead. I was convinced she was dead. But dead or alive, we weren’t sure how to handle the issue with DJ. Which two-by-four to hit him with? That his mother was in all likelihood dead? Or that she was out there somewhere but didn’t care enough to come by or call?

And soon he would be asking more complicated questions. What if he wanted to know why his mother didn’t love him enough to take care of herself? So she could live long enough to be there for him? So she could tell him herself how much she loved him when he was old enough to remember her and to know what love means?

My partner and I discussed these issues late at night when DJ was in bed, thankful for each day that passed without having the issue of his missing mother come up. We knew we wouldn’t be able to avoid or finesse it after another summer arrived in Seattle. As the weeks ticked away, we admitted that those closed adoptions we’d frowned upon were starting to look pretty good. Instead of being a mystery his mother was a mass of distressing specifics. And instead of dealing with his birth parents’ specifics at, say, 18 or 21, as many adopted children do, he would have to deal with them at 4 or 5.

HE was already beginning to deal with them. The last time she visited, when DJ was 3, he wanted to know why his mother smelled so terrible. We were taken aback and answered without thinking it through. We explained that since she doesn’t have a home she isn’t able to bathe often or wash her clothes.

We realized we screwed up even before DJ started to freak. What could be more terrifying to a child than the idea of not having a home? Telling him that his mother chose to live on the streets, that for her the streets were home, didn’t cut it. For months DJ insisted that his mother was just going to have to come live with us. We had a bathroom, a washing machine. She could sleep in the guest bedroom. When grandma came to visit, she could sleep in his bed and he would sleep on the floor.

We did hear from DJ’s mother again, 14 months after she disappeared, when she called from Portland. She wasn’t dead. She’d lost track of time and didn’t make it up to Seattle before it got too cold and wet. And whenever she thought about calling, it was too late or she was too drunk. When she told me she’d reached the point where she got sick when she didn’t drink, I gently suggested that maybe it was time to get off the streets, stop drinking and using drugs and think about her future. I could hear her rolling her eyes.

She’d chosen us over all the straight couples, she said, because we didn’t look old enough to be her parents. She didn’t want us to start acting like her parents now. She would get off the streets when she was ready. She wasn’t angry and didn’t raise her voice. She just wanted to make sure we understood each other.

DJ was happy to hear from his mother, and the 14 months without a call or a visit were forgotten. We went down to Portland to see her, she apologized to DJ in person, we took some pictures, and she promised not to disappear again.

We didn’t hear from her for another year. This time when she called she wasn’t drunk. She was in prison, charged with assault. She’d been in prison before for short stretches, picked up on vagrancy and trespassing charges. But this time was different. She needed our help. Or her dog did.

Her boyfriends and traveling companions were always vanishing, but her dog, Wish, was the one constant presence in her life. Having a large dog complicates hitchhiking and hopping trains, but DJ’s mother is a petite woman, and her dog offers her protection. And love.

Late one night in New Orleans, she told us from a noisy common room in the jail, she got into an argument with another homeless person. He lunged at her, and Wish bit him. She was calling, she said, because it didn’t look as if she would get out of prison before the pound put Wish down. She was distraught. We had to help her save Wish, she begged. She was crying, the first time I’d heard her cry since that day in the hospital six years before.

Five weeks and $1,600 later, we had managed not only to save Wish but also to get DJ’s mother out and the charges dropped. When we talked on the phone, I urged her to move on to someplace else. I found out three months later that she’d taken my advice. She was calling from a jail in Virginia, where she’d been arrested for trespassing at a train yard. She was calling to say hello to DJ.

I’ve heard people say that choosing to live on the streets is a kind of slow-motion suicide. Having known DJ’s mother for seven years now, I’d say that’s accurate. Everything she does seems to court danger. I’ve lost track of the number of her friends and boyfriends who have died of overdoses, alcohol poisoning and hypothermia.

As DJ gets older, he is getting a more accurate picture of his mother, but so far it doesn’t seem to be an issue for him. He loves her. A photo of a family reunion we attended isn’t complete, he insisted, because his mother wasn’t in it. He wants to see her “even if she smells,” he said. We’re looking forward to seeing her, too. But I’m tired.

NOW for the may-God-rip-off-my-fingers-before-I-type-this part of the essay: I’m starting to get anxious for this slo-mo suicide to end, whatever that end looks like. I’d prefer that it end with DJ’s mother off the streets in an apartment somewhere, pulling her life together. But as she gets older that resolution is getting harder to picture.

A lot of people who self-destruct don’t think twice about destroying their children in the process. Maybe DJ’s mother knew she was going to self-destruct and wanted to make sure her child wouldn’t get hurt. She left him somewhere safe, with parents she chose for him, even though it broke her heart to give him away, because she knew that if he were close, she would hurt him, too.

Sometimes I wonder if this answer will be good enough for DJ when he asks us why his mother couldn’t hold it together just enough to stay in the world for him. I kind of doubt it.

4. My Unlikely Pandemic Dream Partner

By Merissa Nathan Gerson

Last March, before my mother flew from Washington, D.C., to visit me in New Orleans, we negotiated how long she should stay. I was having knee surgery after tearing my meniscus and A.C.L. during a Mardi Gras parade, and she offered to help me recover.

She wanted to stay for seven days. I said five days was the most I could handle. In the end, she stayed for 53.

That’s because the pandemic arrived, along with a citywide stay-at-home order. And this dullness set in. We ate in dullness. We watched movies in dullness, learning to alternate between my mother’s desire for old films about war and immigration, and my desire for reality dating shows that she found disgusting. We loathed each other quietly, not yet understanding how to change the dynamic we had built over 38 years.

Like many Americans her age, my mother didn’t take the pandemic seriously at first. It was a team effort for my siblings (in Los Angeles) and me to get her to wear a mask and stay home. I would find foods in the house like ice cream or braided anise-seed cheese, evidence of her escapes to Baskin-Robbins and the local Palestinian grocer.

At first, I balked at her sadness and the collapse of my adult autonomy. My mother had replaced my first caregiver, Abby, a friend and healer from New England, who tended to me like a child before and after surgery.

My mother wasn’t bright-eyed like Abby — yet. Her eyes were heavy. My father had died suddenly only a few months earlier, and she carried a broken heart from room to room like a backpack. I felt bad for needing her and guilty about all the work she had to do to care for me. She already had so much on her plate.

When I bathed for the first time after surgery, I grew faint at the sight of my stitches and started yelling. I expected my mother to zone out, but she rushed in with a stool for my knee and sat down at the foot of the tub, iced coffee in hand. Seeing her there, sitting with me, naked on a trash-bag covered chair, as if it were normal, I began to notice and appreciate how much she loved me.

I was struck by her simple acts of devotion. I had to trust her to lift my leg and help me from bed to crutches to the bathroom, every single time. I had to depend on her to carry my things from room to room, to find my clothes, to feed me. She made eggs and toast and matzo brei, learned how I liked my tea, made my bed and washed my clothes.

I hadn’t let anyone this close to me in years. She was becoming my dream partner.

A food writer, my mother went in cycles testing recipes. She cooked Dutch baby pancakes for a week, was strangely exuberant about her warm homemade hummus another, and made and remade several versions of Iraqi Jewish mujadara, a dish served to mourners, made with lentils, caramelized onions, and rice or bulgur.

I hate cooking for myself. She signed us up for the local C.S.A., ripe with local artichokes and peaches galore. We had fodder for trades.

And then came the emissaries. Josh, who lived behind me, showed up with strawberry jam from Ponchatoula, La. He was so sweet, leaving it 10 feet from where I was sitting on the porch. There was a caveat: “Would you mind,” he said, “if I went into your backyard? My chicken has flown into your loquat tree.”

This was the start of a lot of chicken escapes, and a lot of trading. We gave Josh and his boyfriend, Michael, cake and bread; they dropped off curry and let my mother pick their mulberries.

This was also the start of my mother and me falling in love. She came alive when the neighborhood did, leaving my father in the grave and joining the living as she harvested the mulberries down the street, meeting the neighbors who peeked their heads out the window to speak with her while she picked. She made dried mulberries, mulberry cake, mulberry muffins and mulberry jam. She loved mulberries like they were cocktails. I marveled at her.

Our neighbor, Annie, began coming by to harvest our kumquats and lemons with her two sons. She made us cookies and left them on our porch every week. We left her chili, stew and homemade challah.

Virginia appeared soon thereafter, from across the street. She and my mother began talking at the fence, and that bridged more trades. Virginia brought us ketchup, made us our first masks and then showed my mother her sacred Mardi Gras craft room, where the shoes for the Krewe of Muses were gilded in a den of glitter. She taught my mother about possums and brought us our own flat of Ponchatoula strawberries. We left a portion of smoked leg of lamb in her mailbox when Alon Shaya, a local chef, dropped one off.

The dullness of quarantine gave way to a socially distanced affair, evening dates and all. My mother’s eyes lit up as she shared stories of the day’s encounters over the dinner she made or the sinfully delicious food we ordered from local restaurants. I began to loosen, to lean into the care I felt so guilty for receiving, the three meals a day cooked by my mother, the needing someone, that letting go of an almost too fierce independence I had built over the years.

My mother glowed. She was taking long masked walks alone and exploring New Orleans by foot, discovering the hidden Jewish names in so many graveyards, the horrific Confederate statues and the unreal beauty of City Park.

We eventually started processing our grief, finding space that is so hard to find when two people are grieving simultaneously. Sometimes it was in the middle of the night, like when I heard the screeching of a cat (either dying or mating) and woke her, scared. Or the time our neighbor’s chicken squawked its last breath when a hawk stole it from their yard, took it to my roof, killed it and dropped it outside my window.

Quarantine for us was not boring.

We started to learn that we were grieving two different men. Hers was the husband she met in the 1970s, a partner and friend who went to movies with her and around the world, who emotionally supported her, slept beside her, made space for her career.

And I was grieving the loss of my father, someone a bit more distant, who was mine for only 38 years, and who I ached to have with us on the sofa, laughing at bad TV, enraptured by old movies.

We ordered new clothes for her, as she had packed for only five days and needed things to wear for nearly two months. We started holding hands while watching our strange selection of movies: “Goodbye, Columbus,” “Baby Boom” and “Force Majeure,” or the delight of “My Brilliant Friend,” our companion for a whole week.

This touch between us felt like pulling up from the void. It felt like splicing open hell to have a quiet picnic.

We found a rhythm, her two-hour walks while I taught my Tulane students on Zoom, followed by lunch together and a review of my curriculum. On Sundays, a friend would take her for a bike ride, and later we would put on masks and drive through the empty French Quarter to the Bywater, where we waved to friends from a distance and got cocktails to go.

We had found our way.

When she perked back up, refilled with color and life, I helped her do her makeup and clothes for her Zoom seminars, and we sat at dawn, me in bed, her in the window seat, and talked about loss. But not both of ours at once. We learned how to weave in mulberries and chickens and fresh-picked flowers, how to bake and breathe and listen to the lives we were living, how important it was to be full in order to finally make space to speak of our emptiness.

By May, I was walking again. She started making muffins and stews for me, stocking my freezer. And then one Monday, she put on rubber gloves and a mask and went to the very empty airport to return home.

We had made it through 53 days of coronavirus quarantine. My father was still gone. Her husband was still gone. He wasn’t coming back. And in his absence, with no one else around, my mother and I fell in love with caring for one another.

5. Hear That Wedding March Often Enough, You Fall in Step

By Larry Smith

YES, we were on an idyllic rock on a postcard-worthy cove on the New England coast. O.K., I did have a ring -- seven actually, none with diamonds. Fine, there was fumbling and nervousness and the oh-so-slyly stashed champagne in the vegetable drawer of the refrigerator back in the cottage.

But let's get one thing straight: I didn't say the words. I didn't need to ask. She didn't need to answer. It never mattered.

Will you marry me? Who wants to know? Who cares? Not me. Not her. Is there anyone else, really, whose opinion counts?

Piper and I had been together seven years. What with medical advancements, free-range chicken and Pilates classes, I estimated we were good for 50, maybe 60 more. We didn't need a piece of paper to make what we had more real.

What we needed was to learn Spanish and surf in Costa Rica. We needed to buy an apartment together and discuss light fixtures. Maybe we even needed to breed. We didn't need to get married.

This troubled the usual suspects (our grandparents, our mothers), but it also, to our surprise, concerned the unusual suspects (the pierced, the gay, the younger siblings). At a coleslaw-wrestling contest in Daytona Beach, Fla., a grizzled biker told Piper she was nuts ("What are you doing with this guy, he got money?") and called me an idiot for not sealing the deal ("You better hold on tight, boy, before someone takes her away").

What, exactly, was the problem? We didn't have one.

This wasn't a political statement. We'd been to 27 weddings -- 27! -- in our seven years together. We'd made toasts, danced with stray cousins, coaxed extra bottles of booze from busboys. No one could accuse us of not supporting, with gusto, this hallowed tradition.

This wasn't the fallout of family trauma. My folks are high school sweethearts, married 40 years for better, for worse. Her parents divorced when she was in high school; not ideal but not exactly unusual for someone born in 1969, nor, in her case, the cause of large therapy bills later.

She'd tell you her dream as a young girl never involved a man whooshing her off her feet, shoving a rock on her finger and sending her down the aisle. She'd tell you she's always been tough-minded and independent and never expected to be in a relationship this long. She'd tell you she's shocked it's working out so well. I saw no reason to rock this boat.

Cut to the night before our wedding: let's call it May '06. A cool breeze greets the guests at the rehearsal dinner in a funky cafe in Key West. The mixing and mingling subsides as a playful pastiche of our previous, separate lives is screened at the front of the room. Roll video.

Mine comes on first. The Dennis the Menace youth. Inappropriate uses of the high school P.A. system that would make the Desperate Housewives blush. Kooky Atlantic City summers at my grandmother's house and staying out all hours with a series of playthings she and her best friend, Bunny Bookbinder, definitely didn't approve of. A theme emerges: girls. He loves them. Short, tall, big, small. White, black, Asian. Older, younger. Laurence David Smith is girl crazy. What's more, he himself is no big deal to look at, so he works a bit harder. But he loves it. Look at him chase! Why give this up? Ever?

Now we see him in his mid-30's, living in New York, best place on earth for a dude with a good job and no discernible drug or anger management problems to become acquainted with a lot of women. He could go on like this for years -- 5! 10! -- before settling down with a choice woman in his target demographic. Fun!

Her life story has real glamour, though. Here she is, being born to hippie parents, San Francisco. The brief but memorable child-modeling career. The slow, sure development of a stubborn streak and indifference to boys. The years at an all-women's college. Jobs at rollicking bars. Exploits in Indonesia. Dangerous love. Make no mistake, she's the one always being chased (and rarely caught) in this movie. Theme: Don't fence me in. Marriage? Don't bet your lunch money on it.

The man who loves women and the woman who won't be corralled -- makes for great video.

You say: Tigers never change their stripes.

We say: We're together, we're happy.

Survey says: If it ain't broke, don't marry it.

What happened?

I'm not entirely sure. My path to carrying seven gold rings (one for each year we'd been together) in a hermetically sealed bag as I cautiously kayaked out to that rock was subtle, a combination of personal outlook, impossible-to-define emotional pull, and gut instinct that even now I am still piecing together.

THERE was never a tipping point, no eureka moment when I realized that doing the most traditional thing possible was a good idea. Some guys say they know immediately She's the One. Not me. Whether it's a sweater or software, it takes some time for me to know if I want to keep something, one reason I always save receipts. I can't say there was an instance when I looked into the pale blue eyes of the girl I met over corned beef hash at a cafe in San Francisco and thought, "This is it." Now, after eight years, I know.

When did I know? Was it the way she helped me deal with the death of my grandfather? The relief I felt when she finally answered her cellphone on Sept. 11? That great hike in Point Reyes? Because she sobbed with joy when the Sox finally won? The way my nephews greet her like a rock star when she walks into the room?

Perhaps I should have known right from the start, that morning in the middle of our cross-country trip, when she required one last stop at Arthur Bryant's in Kansas City for a half slab of ribs for breakfast (and 10 minutes into the feast saying to me, "Hey, baby, why don't you pop open a beer?"). Or did I not truly know until seven years later when we found ourselves forced apart for more than a year? Who can say? It's the big moments, maybe, but it's the little moments as much or even more.

I do know one thing: Those 27 weddings had a lot to do with it. They were joyous, righteous, nup-tastic affairs. (As Woody Allen said about orgasms, "the worst one was right on the money.")

The idea of putting our own personal stamp on a tradition we've now seen take so many shapes and forms -- including but not limited to full masses, lobster bakes, white doves, exploding huppahs, gigantic soap bubbles, freezing-cold skinny dipping, and one quasi-orgy -- has become more appealing, not less, with each one.

And what else started to happen at those weddings? More little moments that began adding up to a big reckoning. She pinched the skin of my elbow during a recent "we cannot be hearing this" toast from a father of the bride, and during a particularly beautiful ceremony she gave my hand a little squeeze, her quiet tears landing on both our fingers. And I swear I saw an ever-so-slightly different look in her eyes the lzzast time a perfect stranger questioned my sanity for not locking this lady up.

Slow as ever, yet indeed as sure as it gets, it dawned on me: She wants to get married. And if that's true, then I want to get married. To her. This is perhaps the least original idea I've had in a long time, but I needed to get here myself, on my own terms. And after all these years one thing I actually had going for me was the element of surprise.

So what the hell, let's do it. I still don't believe marriage is the only path to happiness or completeness as a person, but it's the right thing for us. So I asked her. Or, more accurately, what I said, sitting next to her on that silly island in a scene straight out of Bride's magazine, was something about love and commitment and not going anywhere and here's these rings I got you, and if you want actually to make it official, that's cool, and if you don't, that's cool, too. And if you want to have a wedding, I'm into it, and if you don't, who needs it. She's still unclear what it was I was asking, exactly, but when she got done laughing, she said yes. And then she threw off her clothes and jumped in the water.

My friends joke that I've been to 27 weddings and now it's finally time for one funeral -- for my singlehood. Which is sad like any funeral, sure, but this death is no tragic accident. I look at it more like euthanasia I'm performing on myself, a mercy killing.

I'm ready, babe. Pull the plug.