多人英文轮本,该系列Part 1,选自《纽约时报》Modern Love专栏英文故事,同名美剧(豆瓣8.8分)取材。

5个bgm分别对应5个故事,配合bgm效果更佳。

(禁止转载,如有侵权,请联系作者处理)

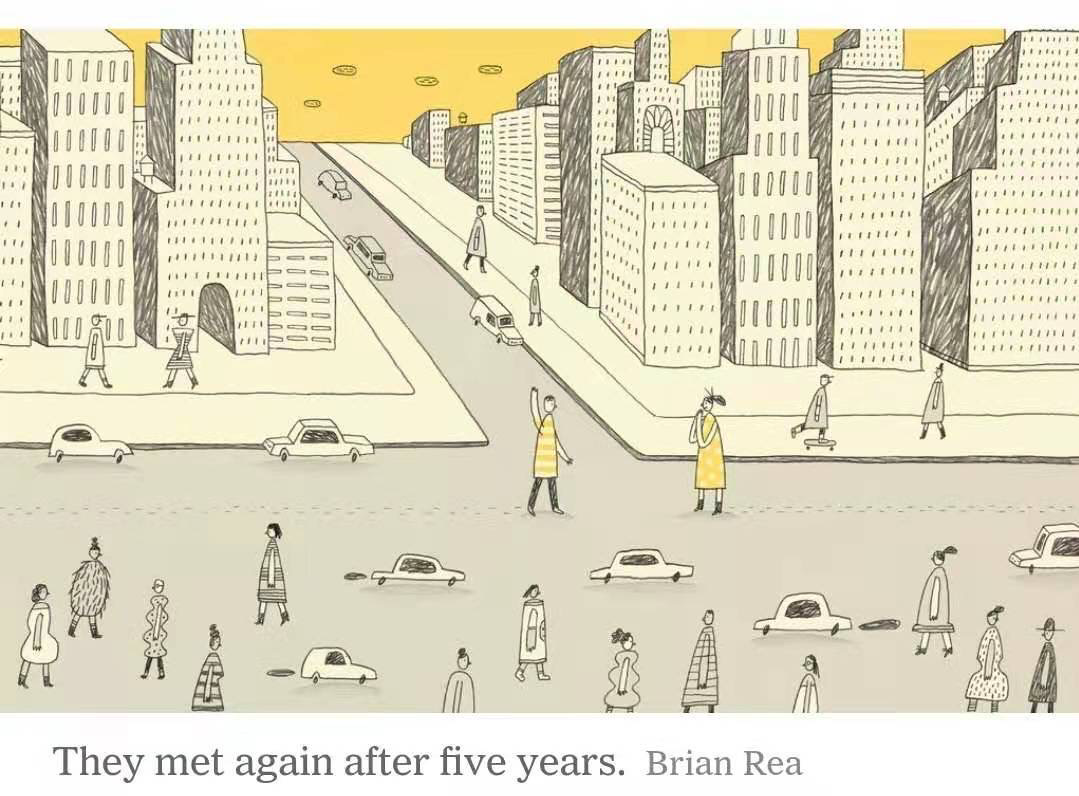

1. Let’s Meet Again in Five Years

By Karen B. Kaplan

When I told Howard that we should meet again in five years to see if we were meant to be together, I thought I was just being practical. My idea was less about romance than hedging our bets.

I was only 18 then, a freshman at Cornell, and he was barely 21. We had dated since September and now it was spring. Soon we would be headed back to opposite coasts, he to San Francisco and me to suburban New Jersey. The impending separation was forcing us to re-evaluate. Our dorm-room conversation went something like this:

Me: “I think finding The One is a matter of person, place and time. What if we’re both the right person but this is the wrong place and time? We’d miss our chance and regret it.”

Him: “So, are you saying we should stay together?”

Me: “No. I don’t want to marry the first guy I’m serious about. I’m saying, let’s give ourselves a second chance. Let’s meet in five years. I’ll be 23, and you’ll be 26. We’ll see if we want to get back together.”

Howard agreed. We settled on meeting at the New York Public Library, near the uptown lion, at 4 p.m. on the first Sunday in April, five years from that spring. We wrote our pledge on a dollar bill, tore it in half and gave each other the half we’d written on.

Meeting in a public place would minimize any unwanted intimacy if things felt awkward. Four o’clock made sense because we could start with a drink, and if things went well, we could proceed to dinner and go from there. If things weren’t going well, we could go our separate ways.

The New York Public Library was a sentimental choice; as English majors, we had spent a lot of time around books. And it was an easy landmark to find, one that was likely to still exist in five years, unlike a restaurant or bar.

Although the first Sunday in April was our original choice, I soon realized that could fall on Easter, and my mother, a firm Catholic, would never abide my heading into New York City that day; we’d be having a family celebration.

So Howard and I took back our half dollar bills, crossed out April, wrote May and handed them back to each other.

And then we failed to break up. In fact, we stayed together that summer and through the whole next school year. It wasn’t until the next semester, when he took a leave of absence and lived in Manhattan, that our relationship finally ended. (I started seeing someone else, he found out, and that was that.)

We had three and a half years before our meeting.

I used that time well. I had relationships, flings, crushes. With a few of those men, I wondered, “Is he The One?” For various reasons, the answer was never “Yes.” Might it have been “Yes” if Howard and I didn’t have our date planned?

Maybe, maybe not. In any case, most of my interactions with men, whether short or long-lasting, only strengthened my sense that Howard probably was The One and that I had been prudent to arrange our second chance.

A part of our agreement that didn’t make it onto the dollar bill was that we would tell no one, a rule I promptly forgot. At some point, I told my best friend. She thought the plan was creative (but felt bad for the guy I was seeing at the time). I also told my mother, which was a mistake.

At the five-year mark, I was living in Minneapolis. I was in a relationship that had been staggering along for months. As for Howard and me, we hadn’t spoken or communicated at all for a couple of years. I vaguely knew of his whereabouts from mutual friends, but this was before cellphones, the internet and email, a bygone era where you could actually lose touch with people and not know how to contact them even if you wanted to.

Nevertheless, a few days before that first Sunday in May, I flew home to the Jersey suburbs for a visit with my mother, planning to head into the city for the weekend. My sister had an apartment on the Upper West Side, and it would be nothing unusual for me to stay with her because I always did when I visited.

But my mother kept suggesting an alternative plan, arguing that it would be better to go into New York when my sister wasn’t working (as a restaurant employee, she was busiest on weekends).

“No,” I said. “I have to go in this weekend. I’m meeting Howard on Sunday.”

That stopped her. “I didn’t know you two were still in touch.”

While I was on the train into Manhattan, my mother called my sister and urged her to keep me from following through, fearing I’d be heartbroken when Howard didn’t show.

When I arrived, my sister said, “You’re trying to live your life like a movie. Real life doesn’t work like that. He’s not even going to remember, much less travel 3,000 miles. You’re setting yourself up for big disappointment.”

I disagreed.

She had to work that afternoon and evening, so I was (quite happily) on my own for the walk from the Upper West Side to Midtown. A few minutes before 4 p.m., I found myself standing across the street from the library, scanning the small crowd in front, when suddenly I saw Howard heading toward the library’s steps.

We saw each other, smiled and waved. I crossed the street and we hugged in front of the lion (Fortitude, I learned later), then sat down on the steps and started talking.

Our conversation lasted two days. Then Howard caught a plane back to California.

It wasn’t immediately “happily ever after” for us. I had to extricate myself from the relationship with the other guy. Howard and I also had to figure out how we were going to live in the same city.

That fall I moved to the Bay Area for a couple of months on a work assignment. A few months later, he moved to Minneapolis, where we stayed for two years before moving to New York. And, yes, once we were back east, we married.

I still resisted calling our story romantic. Friends who had heard the story tended to exaggerate the details, saying things like, “And you didn’t see each other for 10 years?”

Actually, it was a five-year plan. And it was only three years that we were fully out of touch.

Or they’ll say: “And you always knew …”

No, that was the whole point of the agreement. We didn’t always know. Even after the meeting, it took a while for us to move in together. When we moved to New York, we agreed we would have to see how things worked out with jobs before making any promises.

What is true is how the story has helped sustain our relationship through times of trouble. I would have hated to end the story with, “Unfortunately, it didn’t work out.” With a story like that, of course we had to stay together. A romantic past, we’ve discovered, can help keep you belted in place until you find equilibrium.

Still, I insisted the story was about foresight and prudence, not romance. I only shared the story with people who wouldn’t think I was trying to live my life like a movie — who would know the story was about being smart in love, not starry-eyed.

For years, I ended the story with: “I thought I was just being practical in giving us a second chance. It turned out to be a good plan.”

“Well, the plan may have been practical,” a friend said recently. “But the fact that you both showed up: There’s the romance.”

He was right. It was our complete faith in the other person — despite others’ cautions — that defined the romance. We showed up for each other.

We now have been married for 35 years. Howard still shows up for me, and I show up for him. The torn dollar bill is in a frame on his dresser.

2. Take Me as I Am, Whoever I Am

By Terri Cheney

As a bipolar woman, I have lived much of my life in a constant state of becoming someone else. The precise term for my disorder is “ultraradian rapid cycler,” which means that without medication I am at the mercy of my own spectacular mood swings: “up” for days (charming, talkative, effusive, funny and productive, but never sleeping and ultimately hard to be around), then “down,” and essentially immobile, for weeks at a time.

This darkness started for me in high school, when I simply couldn’t get out of bed one morning. No problem, except I stayed there for 21 days. As this pattern continued, my parents, friends and teachers grew concerned, but they just thought I was eccentric. After all, I remained a stellar student, never misbehaved and graduated as class valedictorian.

Vassar was the same, where I thrived academically despite my mental illness. I then sailed through law school and quickly found career success as an entertainment lawyer in Los Angeles, where I represented celebrities and major motion picture studios. All the while I searched for help through an endless parade of doctors, therapists, drugs and harrowing treatments like electroshock, to no avail.

Other than doctors, nobody knew. At work, where my skills and productivity were all that mattered, I could hide my secret with relative ease. I kept friends and family unaware with elaborate excuses, only showing up when I was sure to impress.

But my personal life was another story. In love there’s no hiding: You have to let someone know who you are, but I didn’t have a clue who I was from one moment to the next. When dating me, you might go to bed with Madame Bovary and wake up with Hester Prynne. Worst of all, my manic, charming self was constantly putting me into situations that my down self couldn’t handle.

For example: One morning I met a man in the supermarket produce aisle. I hadn’t slept for three days, but you wouldn’t have known it to look at me. My eyes glowed green, my strawberry blond hair put the strawberries to shame, and I literally sparkled (I’d worn a gold sequined shirt to the supermarket — manic taste is always bad). I was hungry, but not for produce. I was hungry for him, in his well-worn jeans, Yankees cap slightly askew.

I pulled my cart alongside his and started lasciviously squeezing a peach. “I like them nice and firm, don’t you?”

He nodded. “And no bruises.”

That’s all I needed, an opening, and I was off. I told him my name, asked him his likes and dislikes in fruit, sports, presidential candidates and women. I talked so quickly I barely had time to hear his answers.

I didn’t buy any peaches, but I left with a dinner date on Saturday, two nights away, leaving plenty of time to rest, shave my legs and pick out the perfect outfit.

But by the time I got home, the darkness had already descended. I didn’t feel like plowing through my closet or unpacking the groceries. I just left them on the counter to rot or not rot — what did it matter? I didn’t even change my sequined shirt. I tumbled into bed as I was, and stayed there. My body felt as if I had been dipped in slow-drying concrete. It was all I could do to draw a breath in and push it back out, over and over. I would have cried from the sheer monotony of it, but tears were too much effort.

On Saturday afternoon the phone rang. I was still in bed, and had to force myself to roll over, pick it up and mutter hello.

“It’s Jeff, from the peaches. Just calling to confirm your address.”

Jeff? Peaches? I vaguely remembered talking to someone who fit that description, but it seemed a lifetime ago. And that wasn’t me doing the talking then, or at least not this me — I’d never wear sequins in the morning. But my conscience knew better. “Get up, get dressed!” it hissed in my ear. “It doesn’t matter if she made the date, you’ve got to see it through.”

When Jeff showed up at 7, I was dressed and ready, but more for a funeral than a date. I was swathed in black and hadn’t put on any makeup, so my naturally fair skin looked ghostly and wan. But I opened the door, and even held up my cheek to be kissed. I took no pleasure in the feel of his lips on my skin. Pleasure was for the living.

I had nothing to say, not then or at dinner. So Jeff talked, a lot at first, then less and less until finally, during dessert, he asked, “You don’t by any chance have a twin, do you?”

And yet I was crushed when he didn’t call.

A couple of weeks later, I awoke to a world gone Disney: daffodil sunshine, robin’s egg sky. Birds were trilling outside my window, a song no doubt created especially for me. I couldn’t stand it a minute longer. I flung back the covers and danced in my nightie — my gray flannel prison-issue nightie. I caught one glimpse of it in the mirror, shuddered, and flung it off, too.

I rifled through my closet for something decent to wear, but everything I put my hands on was wrong, wrong, wrong. For starters, it was all black. I hated black, even more than I hated gray. Redheads should be true to their colors, whatever the cost. I dug deeper, and there, shoved way in the back, was a pair of skin-tight jeans and something silky and sparkly and just what I needed: an exquisite gold sequined shirt.

I slipped it on and preened for a minute. Damn, I looked good. Then I tugged on the jeans. I had gained a few pounds during the last couple weeks of slothlike existence, but once I yanked really hard, they zipped up fine. Although something was sticking out of the pocket: a business card, with a few words scribbled across the back: “Call me, Jeff.”

Jeff?

Jeff! I kicked the nightie out of my way and grabbed the bedside phone. Was 6:30 a.m. too early to call? No, not for good old Jeff! It rang and rang. I was about to give up when a thick, sleepy voice said “Hello?”

“It’s me! Why haven’t you called?”

It took a while to establish who “me” was, but eventually he remembered. “You sound different,” he said. “Or no, maybe you sound more like yourself. I’m not sure. It’s so early.”

Soon I had him laughing so hard he got the hiccups and had to get off the phone. But before he did, he asked me out for Friday, three nights away.

No, I insisted, it had to be tonight, or even this afternoon. I didn’t want to lose another chance to get to know him. I knew that Cinderella had only so much time left at the ball.

We compromised on dinner that evening at 8. I spent the afternoon ridding my house of all evidence of depression. I soaped and scoured and dusted and vacuumed, using every attachment, even the ones that frightened me. Then I ran out and bought a dozen Casablanca lilies to hide the smell of ammonia and bleach.

When the house looked perfect, I turned on myself with the same fury. I buffed and polished and creamed and plucked and did everything in my power to recreate Rita Hayworth’s smoky allure in “Gilda.” As I was shadowing my eyes, I remembered her poignant line about the movie: “Every man I’ve known has fallen in love with Gilda, and wakened with me.” It gnawed at me, to the point that my hand started trembling and I couldn’t finish applying my mascara.

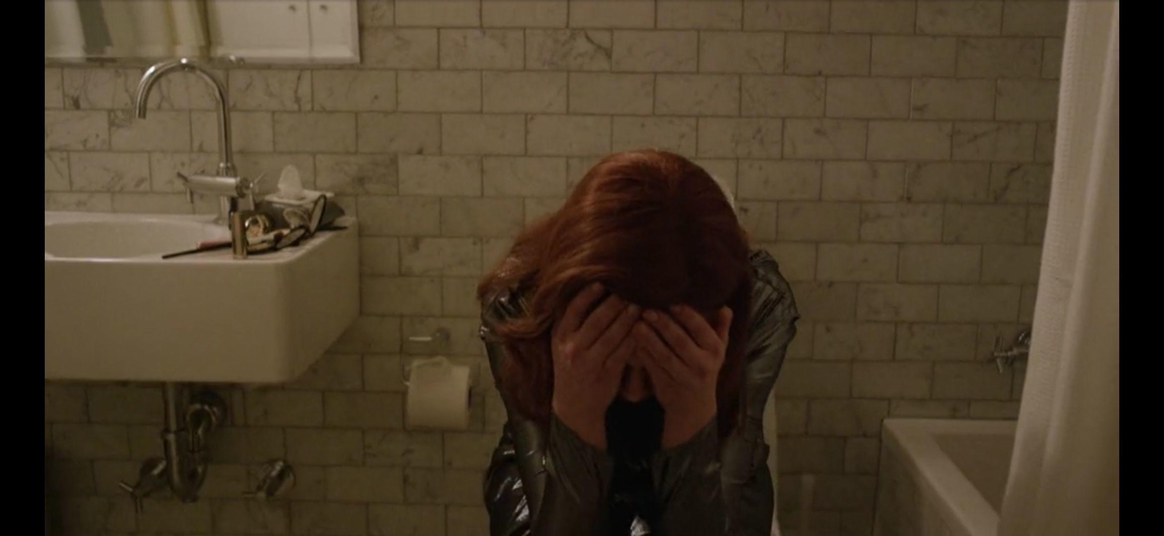

Suddenly I didn’t look radiant. There were lines around my mouth and a hollowness to my eyes that aged me 10 years. My skin, despite the carefully applied foundation and blush, was so deathly pale I recoiled from my reflection.

I sat on the toilet and started to cry. I had met the enemy enough times to know it by sight. Not now, I prayed. Please not now. Globs of mascara ran down my cheeks, and I wiped them away, heedless of the streaks they left. It was 7:57. I had three minutes to wrestle my brain chemistry into submission. Oh, sure, I knew there was another option. I could tell Jeff what was going on. But this was a man who didn’t even like his peaches bruised. What would he think of a damaged psyche?

Maybe he would understand. Maybe I would find the courage. Maybe they would invent a cure.

Maybe, but not tonight. As the doorbell rang and rang, I huddled in the bathroom, shivering. I was terrified — not just of Jeff finding me there, but of me never once finding love.

When it was finally quiet, I rinsed off the rest of my mascara and tossed my cocktail dress into the hamper. Then I buttoned up my gray flannel nightie, and settled in for the long night to come.

I never heard from Jeff again.

That was five years ago — five long years of ups and downs, of searching for just the right doctor and just the right dose. I’ve finally accepted that there is no cure for the chemical imbalance in my brain, any more than there is a cure for love. But there’s a little yellow pill I’m very fond of, and a pale blue one, and some pretty pink capsules, and a handful of other colors that have turned my life around. Under their influence, I’m a different person yet again, neither Madame Bovary nor Hester Prynne, but someone in between. I have moods, but they don’t send me spinning into an alternate persona.

Stability, ironically, is so exciting I have decided to venture into dating again. I have succumbed to pressure from friends and signed up for three months of a computer dating service. “Who are you?” the questionnaire asks at the start.

I want to be honest, but I don’t know how to answer. Who am I now? Or who was I then?

Life seems so much tamer these days: deceptively quiet, like a tiger with velveted paws. Every so often the sun shines too bright and I think, for a moment, that I own the sky. I think, how wonderful it was to be Gilda, if only in my own mind. But then I remember the price of the sky. So I take off my makeup, rumple my hair and go to the supermarket in sweats. The gold sequined shirt languishes in my closet. I’m thinking of giving it away.

Not just yet.

3. At the Hospital, an Interlude of Clarity

By Brian Gittis

There is never a good time to fall off your couch onto a martini glass, nick a major blood vessel and begin losing a dangerous amount of blood, but having this happen in the middle of a promising date is an especially bad time. Nothing breaks the mysterious spell of blossoming attraction faster than spurting blood.

I demonstrated this last spring while on my fourth date with a Brazilian woman so beautiful I was almost afraid of her. After dinner in a homey Italian restaurant, we walked back to the apartment I had just moved into in Brooklyn. Living in the city for the first time without roommates, I was eager to take advantage of my newfound privacy. And things were going well. There’s something romantic about drinking from fancy glasses in an unfurnished room full of unpacked boxes. Miles Davis’s “In a Silent Way” spun on the record player.

I was amazed to have gotten this far. As my friends were sick of hearing, it made no sense to me that a gorgeous woman in her early 20s who spoke four languages and had lived on three continents was spending her Saturdays with me, a 31-year-old bookish type from Pittsburgh.

Each outing felt as if I were sneaking into an exclusive club, and at the end of the night I always feared I would be discovered and asked to leave. I realize that meeting someone wonderful is the whole point of dating, but actually being with someone wonderful can be too stressful for me to enjoy.

This stress is typical for me. I have been on anti-anxiety medication for about 10 years, and on dates I’m constantly asking myself: “Was that the wrong thing to say? Do I seem nervous? Will obsessing about being nervous make me appear more nervous?”

Not unusual questions to ask yourself when meeting new people, but for me they can be paralyzing. Any brain space left for experiencing the date itself is woefully small. Even if the evening goes well, I often appreciate it only later and from a distance, as if it had happened to someone else — like dating in the third person.

So far my success with this particular woman had been an exercise in ignoring the reality of it, which apparently also led me to ignore the reality of my surroundings in general. As she unraveled herself from our embrace on the couch to use the bathroom, I fell onto the after-dinner drink she had left on the floor, the glass slicing into the soft underside of my upper arm. When I looked down, I glimpsed my exposed triceps and more blood than I had ever seen in my life. The cut had gone nearly to the bone.

This is not the first time a date ended with me in the emergency room. I seem to have a knack for it. My college girlfriend once served undercooked chicken that gave me hallucinations and a fever of 104. Years later, my attempt to cook breakfast for another woman ended in second-degree burns after I managed to set fire to a paper towel. But the severity of this injury, its unfortunate timing and the fact that I was naked all broke new ground.

In the ambulance, the emergency medical workers held together my arm, but their questions threatened to unravel my subterfuge as an acceptable mate to this accomplished young woman.

“How old are you?” one asked, which put our substantial age difference — something we had not yet talked about — suddenly under a spotlight.

“Are you on any medication?”

“Antidepressants and Klonopin,” I reluctantly answered.

Then, to her: “Is he your boyfriend? Your friend?”

Long pause. “Boyfriend,” she blurted uncomfortably. Then, an instant later, “Friend.”

Even though I was riding in an ambulance to surgery, that one still stung.

To the entertainment of the hospital’s overnight staff, I was still half-naked when I arrived. My date had managed to get pants on me while we waited for the ambulance, but as I hadn’t been able to let go of my arm at the time, my shirt would go on only halfway. Being wheeled into surgery like this, alongside a woman in a sexy dress, pretty much screamed “sex injury.”

The next hour was a chaotic blur of X-rays, questions I struggled not to panic about (why does this waiver form ask for my religious preference?) and several doctors’ disconcertingly wide-eyed reactions to my injury.

When I asked, “I’m not going to lose my arm, am I?” the answer was a troubling, “I don’t think so.”

A brusque surgeon with a pitiless stare prodded me as he mumbled about my case to a flock of residents. I couldn’t hear everything, but “seven centimeters” and “arterial” came through loud and clear.

Physical humiliation was next on the agenda. Before the operation, my date got to watch a nurse move my pasty, fluorescent-lit body out of my bloody jeans and into a hospital gown. I pictured us sitting at dinner a week from now, this unflattering snapshot of me hovering between us as I pointed at what I wanted on the menu to the waiter with my hook arm.

Then it was time. I remember that the lights in the operating room were very bright, and I remember being told they were about to start the anesthesia. And suddenly: oblivion.

I awoke in a haze. My arm, and my date, were both still with me. The operation had gone well, but protocol required me to stay in the emergency room for six more hours. This registered, briefly, as a terrifying amount of time for a woman and me to be left alone with no dim lighting, no alcohol, no movie to watch or appetizers to eat, and no escape hatch in the event of awkwardness.

Anxiety visits some people in violent bursts, like an electrical storm. For me, it creeps in gradually and insidiously, like a thickening fog. When the fog becomes dense enough, it causes a scary, dreamlike sensation that my psychiatrist calls “derealization,” where I kind of shut down and can no longer really function in a social situation.

That moment in the hospital should have been one when the fog began its creep, but for some reason it stayed away. I’ll never know if my calm was psychological (a cocktail of adrenaline, morphine and utter relief) or physiological; after six hours of unbroken embarrassment and fear, I was simply too exhausted.

Whatever the reason, I felt fine. My thoughts were clear and unencumbered. My date’s eyes stared into mine with an uncomplicated tenderness that made my head swim. It was as if we had jumped forward years, and the anxieties and gamesmanship of our early dates were a quaint and distant memory. This, I thought, is what it’s like to be with this woman. Neither of us had changed, but I was in a different world.

Those six hours sailed by gloriously. We traded hospital stories and endless jokes about martini glasses. We talked about books and our families. We came up with an absurd screenplay idea, a horror movie set in a hospital. I was talking and laughing and effortlessly connecting with one of the most beautiful women I had ever seen, a woman I was truly falling for.

When I was finally released, our midmorning cab ride back to my neighborhood felt like a lucid dream. We ate egg sandwiches in the park and returned to find the familiar surroundings of my living room splattered with blood. Through a haze of sleep deprivation and residual morphine, I felt like a ghost returning to the scene of my own murder.

As we stood there, mopping up bloody footprints with our Swiffers, surrounded by wadded-up pink paper towels, I thought, “Either you will never see this woman again, or she will stick around a long time.”

Neither happened. I would like to be able to say my story ends in an epiphany, with the end of my anxiety and the beginning of an enduring relationship. But the reality is she left me about a month later. Not because she had found me repulsive in the fluorescent light of the hospital, but for a more conventional reason: She missed her ex-boyfriend.

Sometimes when a guy really likes a girl, he gets a tattoo on his arm. I got this prominent scar instead. But there are times when I finger its deep groove (a new nervous tic), those six beautiful hours in the emergency room flicker in my head, and I am reminded how close I am to an alternate world in which I am happy, a world that occupies the same space as this one but is somehow distinct from it. And while that better world may be difficult to find, it is as close to me as the air in front of my face.

4. When the Doorman Is Your Main Man

By Julie Margaret

It was summertime in Manhattan, dark and balmy, almost midnight, on the Upper West Side. He and I rounded the corner from Amsterdam. Drinks had gone well. Walking me home, he held my hand. Tipsy, I said, “You can’t come up,” and stopped near a stoop.

“I don’t want to,” he said coyly, placing his hands on my waist, drawing me close. “But I do want to see you again.” He smiled.

I smiled. “What I mean is, if you want to kiss me good night, it has to be here.” We weren’t even close to my building.

“But I thought you lived in ——” he said, craning his neck to look for street signs “——the 90s?”

“I do.” I started to stammer, to try to explain. “I do, but see, he knows we’re on our first date, and there’s a window he can see out of onto the sidewalk, and sometimes he’s waiting. If I’m too late, he can get worried.”

“Who?” my date asked, looking concerned. “Who can see us?”

“Um,” I hedged.

“Your boyfriend?”

“No.”

“Your dad?”

“No, no. It’s hard to ——”

“Your husband? You’re married?”

I sighed and shrugged, flying my freak flag, ruining the moment. I took a deep breath. “My doorman.”

Guzim was my doorman, and ours was a common and unsung friendship, that between women living in New York, single and alone, and the doormen who take care of them, acting as gatekeepers, bodyguards, confidants and father figures; the doormen who protect and deliver much more than Zappos boxes and FreshDirect, not because it’s part of the job, but because they’re good men.

“I don’t like him,” Guzim said of a new guy I was dating two months later. He whispered this over the intercom.

I entered the lobby and saw them outside, my doorman and my date on the sidewalk, laughing and chatting. My date turned to flick his cigarette away, and Guzim took the moment to shoot me a look: He had gotten the scoop and was already wary.

I waved goodbye as my date and I walked off. When I glanced back, Guzim shook his head. I rolled my eyes. What did he know? What could he tell from a 10-minute talk?

My date turned out to be sexy and funny, spoke gorgeous Hebrew and partied too much. And so I agreed to a second drink and saw him again, and again, as autumn drew on. I was always attracted to bad boys.

Guzim wasn’t a bad boy. He was kind and well mannered, a gray-haired cross between Cary Grant and George Clooney. Born in Albania in the mid-1940s, he hailed from an educated military family; his father had been an army general. When Guzim was 19, the communist leader Enver Hoxha’s secret police arrested and interned his family, accusing them of treason.

For 20 years, he lived in a labor camp, forced to farm in a remote area, not unlike Stalin’s gulags. “My whole life as a young man,” he said to me once. He never married. Never had children.

At 39, he was finally released, and the United States granted his family asylum. He found a job as a white-glove doorman in New York. Whenever I asked him how he was, on any day, at any hour, he always said, “No complaints.”

This was his mantra.

On Halloween night that same year, I walked home again, this time alone, from the 24-hour CVS. I couldn’t sleep. In pajama bottoms, T-shirt and Uggs, I skipped up the steps into the lobby, a white paper bag clenched in my hand.

Hidden inside was a pregnancy test.

Guzim was resting on his usual stool, half-on, half-off, and looked up from his New York Post.

“What?” he said.

“What?” I said. “Nothing.”

“What is it?”

“Nothing.” I sailed past and held up the bag. “Headache. Tylenol.”

“No,” he said in a drawn-out way, shaking his head, folding his newspaper closed.

I couldn’t fool him.

I stopped and looked around. No one was in the lobby. Fine. It was well after midnight, so I doubled back. “I think, I don’t know ——” I bit my lip. “I missed a, you know.” My face contorted, and I started to cry.

Guzim waited, then said, “The Israeli?”

“Yes! And I don’t even like him,” I said, wiping my tears. “He’s a liar. I can’t spend the rest of my life with him.”

“So don’t,” Guzim said, straightening the cuffs of his uniform jacket. We stood and talked for two more hours.

I was distraught. I thought I had been safe, counted the days and done the math, used protection — most of the time. “How did this happen?” I stupidly asked.

“How?” Guzim said with a wry smile. “Come on. It’s life

Two weeks later, I told the father. He seemed at once delighted and horrified. A few weeks later, he even proposed.

I politely declined. He didn’t want to be a parent. Not really. We didn’t want to marry each other. We both knew the truth.

I said I’d raise the baby myself, and he could be involved as little or as much as he wanted to be. He was off the hook, as long as we kept the drama at bay and stayed in touch. We three would be friends, if not family. He agreed.

Three months later and starting to show, I broke the news to everyone else. My Catholic parents, married over 40 years, feared for my future as a single mother. I didn’t blame them. My girlfriends — married and single, mothers or childless — were mostly supportive.

But I became fodder for gossip: Who was the father? Did I dump him, or did he dump me? Valid questions, sometimes asked to my face, sometimes not.

But down in the lobby, Guzim was there with no dog in the race. I wasn’t his daughter, sister or ex. I wasn’t his employee or boss. Our social circles didn’t overlap. Six days a week, he stood downstairs, detached but also caring enough to be the perfect friend, neither worried nor pitying.

It was he who signed for the crib when it came, for the onesies, bottles and boxes of diapers. It was he who asked how I felt every day. I saw the Israeli every few weeks.

Guzim and I talked a lot over those nine months, and his worldly perspective comforted me: more European than tristate, more Cold War than 21st century and grounded in gratitude.

His stance was resolute. He upheld and honored me for my choice, and protected my dignity and self-esteem. I was still young, he reminded me. I could still meet a man and get married. I had a master’s degree, a job, savings.

So what if I wasn’t married? Look at the world. Worse things had happened in history. Please. We would be fine. My baby was a gift.

In August, while I was away for the weekend, my water broke early, and I gave birth in Providence, R.I. Two days later, my parents picked me up and drove me south on Route 95 to the Upper West Side and home.

When my father pulled up, Guzim knew the car. He skipped down the steps and swung the back door open wide. Somehow he knew what was waiting inside.

I climbed out, exhausted and teary. We hugged. I turned back, unclipped the car seat and pulled it out. We both gazed at the sleeping newborn, impossibly pretty.

“Beautiful,” he said. “Wonderful job.”

Nine days later, the Israeli left for good. His father was sick back home, he said. But we were friends and on good terms, and for the next year, I emailed him photos. He called and we laughed as he kept me awake during those first long, sleepless months.

But Guzim’s was the face we saw every day, the man who said good morning and good night to my girl, who smiled and cooed and remarked on her growth, her smile and her first words.

The Israeli kept in touch for over a year and then disappeared. No more emails or calls. I’d send photos, and he’d send silence.

My daughter held a special affection for Guzim, almost as if she understood the role he had played as someone who welcomed her into this world with open arms, an open heart, ready and willing to guard and protect her, just as he had guarded and protected her mother.

Once she could, she’d run down the sidewalk, arms outstretched, and he’d catch her up into a big hug.

Her father doesn’t call or visit, and we don’t call or visit him. But we visit Guzim.

We live in California now, but when we’re in New York, we drop by the building, hoping to find Guzim at his post. Sometimes he is. Sometimes he isn’t. But we always check.

And when we find him and he asks how I’m doing, I look at my girl and say, “No complaints.”

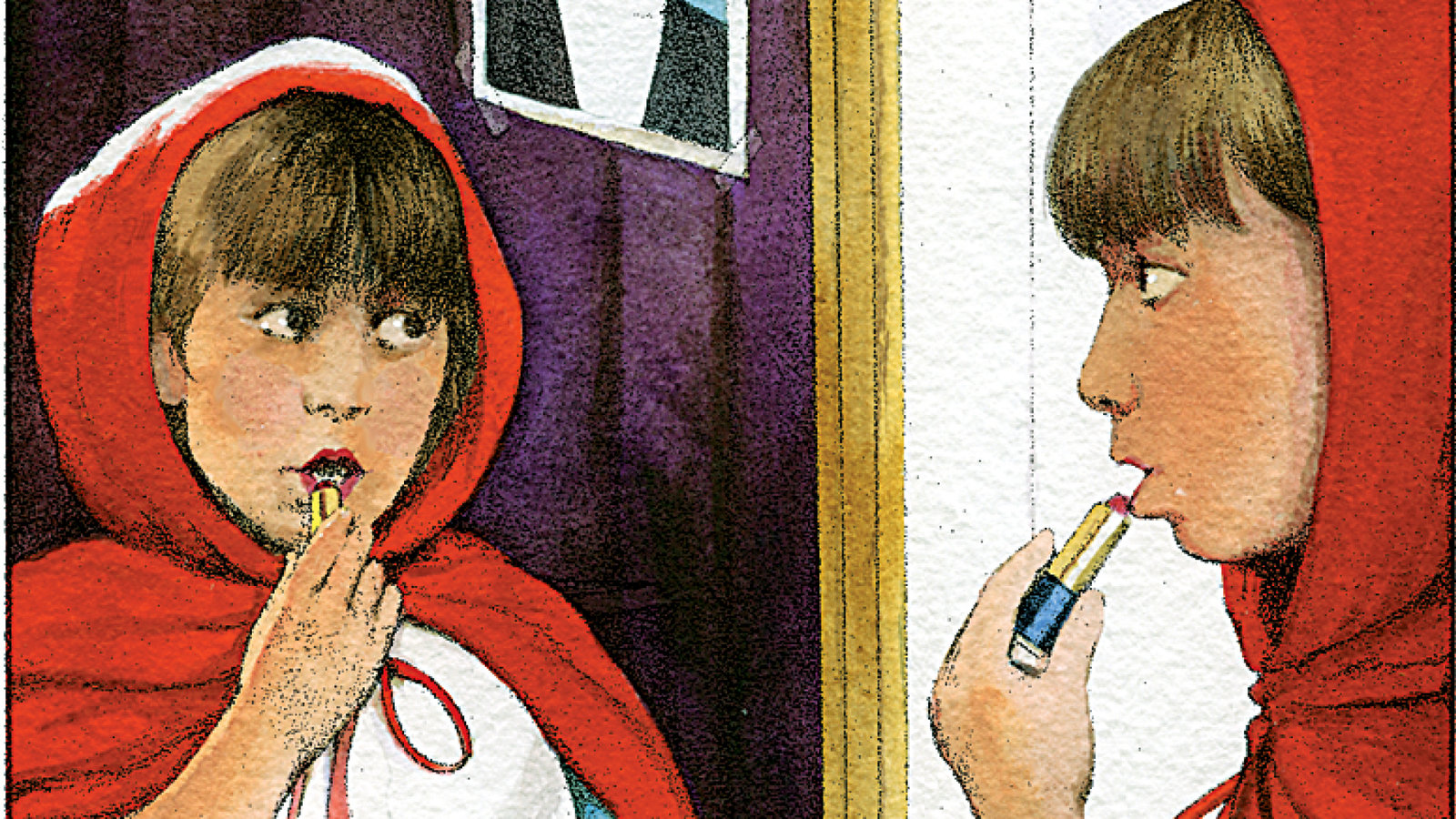

5. So He Looked Like Dad. It Was Just Dinner, Right?

By Abby Sher

THERE was this professor named Andrew who studied artificial intelligence. He was very handsome, in a professorial way. He wore gray turtleneck sweaters and smelled like mint aftershave and old books. He was 55 and recently divorced for the second time. He was my father.

He wasn’t really my father. My father died when I was 11. But Andrew was handsome like my father. He whistled like my father. He had sideburns with little touches of silver, like my father. And he was the only other person besides my father who ever called me by my full name, Abigail. It means father’s joy. People usually just call me Abby.

The first time I saw Andrew was at a staff meeting. I don’t know exactly why I was at the meeting. I was working for the university’s research lab as a “content specialist.” My job was mostly copying papers about studies on brain activity. On busy days I collated and stapled.

During the meeting I watched Andrew lean back in his chair. His eyes were dark gray, like his sweater. He was biting his lower lip and listening intently. He looked like a little boy and a grown man at the same time. He glanced up and caught me staring at him. He smiled.

The next day I saw him by the copy machine. He was walking back into his office. His door was open, and there was classical music playing softly, because he was a professor. The light that spilled from his doorway was warm, and I could hear him humming along with a violin. I wanted a reason to go inside, to see his desk, his books. Maybe he had a potted plant? Framed pictures of his past?

Later that week I saw him at the coffee shop in the basement of our office building. He had a large coffee and large hands. I said hello.

He said, “Abigail, right?”

“Yes.”

We just stared at each other. He looked like he might leave, so I said: “Oh wow! You like coffee? I like coffee too.”

He laughed. He had a soft laugh. His teeth were strong looking.

Pretty soon I was going to that copier by Andrew’s office all the time. Often I had nothing to copy, so I would make copies of my driver’s license, and then make copies of the copy. By the fifth copy my face was just two eyes peeking out of a blizzard.

One day, when I was standing by his door, copying my hand, Andrew came out and stood next to me.

“Do you like duck?” he asked.

“Hmmm, duck,” I said. “Who doesn’t like duck?”

“So would you like to have dinner sometime?”

We made plans for the next Tuesday.

Tuesday afternoon I went into his office when he was out and wrote my address on a scrap of paper. I left it by his daily planner. Notes are cute when you still have braces and are just discovering lip gloss and boys. Notes are different when you’re leaving them on a mahogany desk with an ashtray and a glass paperweight. I folded my note tightly and wrote “Andrew” in script on the front. Then I made sure the hall was empty before I walked out of his office.

I was living with my best friend, Tami. We lived above an all-night diner and had plans to write a movie together. We were supposed to tell each other everything. That’s what best friends do. But I didn’t want to tell her about Andrew. I thought there was something ugly about it.

I had told her vaguely about having had an interesting conversation with an older professor at work who studied robots. She said he sounded cool. Then I told her I might get dinner with him some time. She said that sounded creepy. So when I got home from work on Tuesday, I tried to get changed and out the door before Tami came home.

I put on my blue velour pants and picked out an eggshell-colored sweater that clung to my chest. My father had never seen me developed. I was still confused and embarrassed by my new tufts of hair and the sour smell in my armpits the summer he died. I stared at my reflection in the mirror. The whole thing didn’t make much more sense to me now, at 21.

The door opened as I was putting on eye shadow.

“I got all the leftover pastries,” Tami said. She worked at a coffee shop. That’s where our movie would probably take place, so we thought of it as a research position. She looked at me. “What are you doing, Abby?”

“I told you. I’m having dinner with that professor guy.”

“You said you might go out sometime. You didn’t say you were going out.”

“It’s nothing big.”

“It’s a date.”

“It is not.”

“Then why are you wearing eye shadow?”

“I’m starting a new habit.”

“It’s a date, Abby.”

“It’s not a date. It’s a Tuesday night.”

Her voice got high and loud: “He’s 30 years older than you. He could be your dad.”

I got even louder: “Shut up! We’re just going to have duck.”

Andrew picked me up in his navy blue Saab. It had leather seats with coils that warmed you in the winter. Andrew asked if I was warm enough, and I said yes. He dodged every pothole, swinging through a series of turns with only one palm on the wheel. We stopped at a light. He turned and looked at me. I did a fake sneeze to avoid making eye contact.

“You look sensational,” he hollered over the classical music. He patted my knee. It didn’t matter that it was a Tuesday night. This was a date.

WE arrived at Andrew’s building and got in the elevator. There were mirrors on all sides, so I decided to look at my feet. Andrew lived on the 14th floor in a beautiful apartment with tulips rising from tall, clear vases and the lights of the city blinking through the windows. Everything was on but turned down low, so the violins playing and the duck sizzling and the tulips tuliping would all mind their own business while we got to know each other.

I hopped up on one of his marble counters as those cute girls do in sitcoms. Andrew handed me a cracker with Brie on it. He lifted it to my lips and leaned in so close that my breath got caught under my ribs. I didn’t want him that close, so I shoved the cracker into my mouth and said: “Mmmm. So what are we having besides duck?” Pieces of cracker flew out of my mouth.

Andrew laughed. “You’ll see.” He kissed my neck quickly. Then he went back to stirring something in a pot.

We had slim glasses of chilled white wine, and I stayed on the counter while Andrew cooked. I watched the back of his neck where his dark hair faded into his pink skin. He turned around and had me taste the orange-honey glaze. His eyes focused on my mouth as my lips covered the spoon, and I knew we were here in this moment for completely different reasons. I vowed to eat dinner and then ask him to take me home.

We had duck with steamed broccoli and creamy risotto that melted on my tongue. We talked about artificial intelligence and the role of pattern recognition in early education. When I stood up to clear the table, the floor wobbled. I concentrated on walking carefully to the sink and started rinsing off the dishes. That had always been my job at home. But Andrew shut off the water and asked me if I wanted dessert.

He had an espresso machine and said he wanted to show off. So I said I’d take a cappuccino, and then I excused myself to go to the bathroom.

I looked at the girl in the mirror and said: “Calm down. I’m going home.”

Then I heard Andrew: “Come here! I want you to hear this CD.”

He wasn’t making coffee after all. He was in the bedroom, lying on the bed. He’d taken his shoes off and wore tan old-man’s socks that were embroidered with tiny golf clubs. He was looking at the ceiling and listening to something so sad on his stereo. It sounded like a cello crying.

“Schumann wrote this for his wife before he went mad,” he said. Then he held out his hand.

I stayed in the doorway. “I need to go home now.”

“Really?”

“Yes.”

“I promise I’ll take you home,” he said. “Just listen to this one piece.”

He waited for me to take his hand. I did.

I lay on the bed next to him; he put his arm over me and we sort of spooned. He had a gray comforter. He was a gray comforter. He was my father. And we listened to that piece Schumann wrote for his wife. The whole thing. I loved being pressed into that moment, with his breath tickling my ear, still sweet with wine and orange and honey. I stared out his window at the lights from the downtown Y.M.C.A. and I tried to hear only that moaning cello and to see only the light and dark of the night sky.

When the music stopped, Andrew whispered into my hair, “What do you want to do now?”

I wanted to have him hold me and count all the faces in the moon. Or tell me the story of how I first learned to use chopsticks when we ate noodle soup at Rockefeller Center. I closed my eyes and imagined him sitting in his maroon easy chair, his potbelly almost touching his knee. I listened for his boom-skedada-boom-skedada one-man jazz band.

But that moment had already happened 10 years before. And Andrew didn’t have my dad’s potbelly and didn’t smell like cocktail onions and Tums, and I wasn’t his little girl, and this wasn’t my home.

I was 21 years old. Not a little girl at all.

So I said, “Please take me home now.”

I felt him sigh as he rolled away from me and put his feet on the floor.

“Okey-doke,” he said. He stood up and turned his stereo off. There was nothing more to say.

And so Andrew took me home.