剧本角色

Bohr

男,0岁

这个角色非常的神秘,他的简介遗失在星辰大海~

Margrethe

女,0岁

这个角色非常的神秘,他的简介遗失在星辰大海~

Heisenberg

男,0岁

这个角色非常的神秘,他的简介遗失在星辰大海~

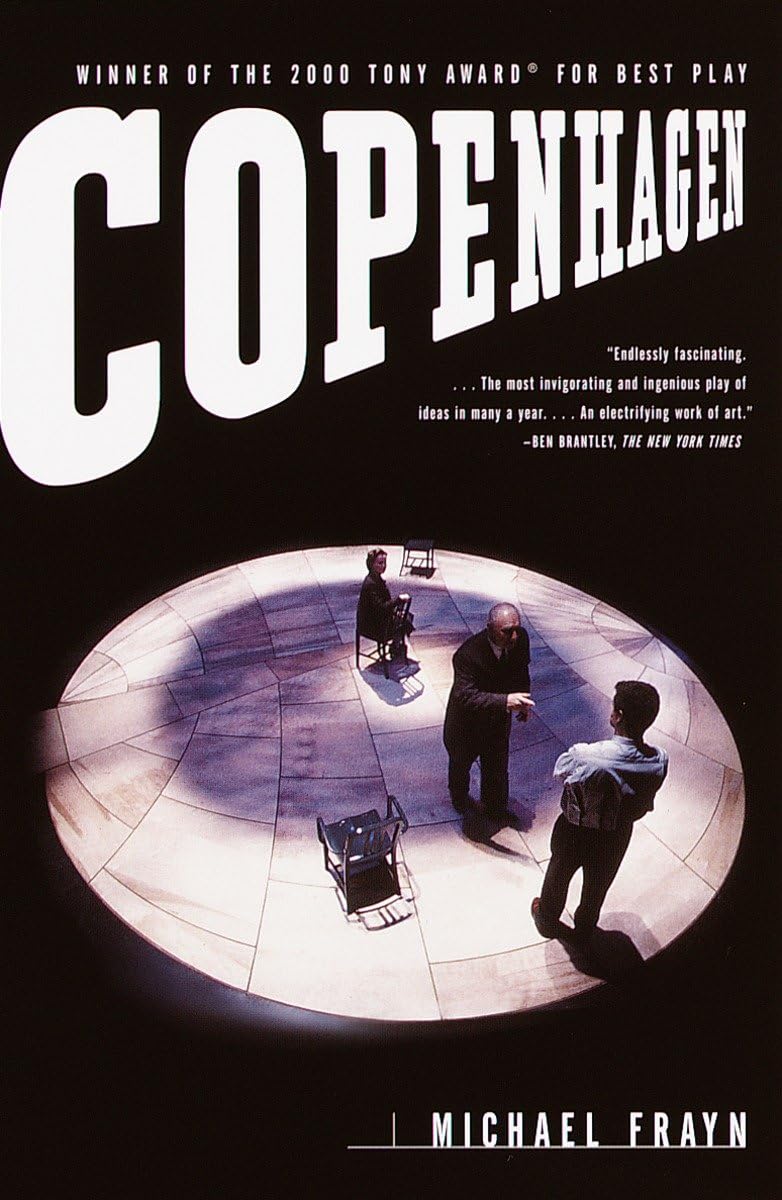

《哥本哈根》是迈克尔·弗雷恩创作的戏剧,基于1941年在哥本哈根发生的一次事件——物理学家尼尔斯·玻尔和他的学生维尔纳·海森堡之间的会面。该剧于1998年在伦敦国家剧院首演,并上演了超过300场

版权归属为迈克尔·弗雷恩,如有侵权,联系作者处理

关于话剧哥本哈根:

天堂,或许是地狱。三个灵魂聚在了这里。

他们谈1941年的战争,哥本哈根9月的那个雨夜,挪威滑雪场的比赛,纳粹德国的核反应堆,同盟国正在研制的原子弹;他们谈量子、粒子、铀裂变和测不准原理,还谈贝多芬、巴赫的钢琴曲;他们谈战争时期个人为自己祖国竭尽全力的权利,炸弹扔下后城市里狼藉扭曲的尸体。

他们谈这谈那,最想说清的却是两个影响了世界物理学进程的诺贝尔获奖者沃纳·海森堡和尼尔斯·波尔在1941年的哥本哈根会面——谜一样的会面。

有关角色详情:

尼尔斯·玻尔(Niels Bohr)

身份:丹麦物理学家,量子力学奠基人之一,诺贝尔物理学奖得主。性格与特质:

理性与包容:以深邃的哲学思考和科学直觉著称,善于在争论中调和矛盾(如提出“互补性原理”)。矛盾与挣扎:在战时面对旧友海森堡的来访时,既试图保持科学家的客观性,又因国家立场与个人情感陷入冲突。父性形象:被海森堡视为学术导师和精神父亲,但战后因理念分歧渐行渐远。剧中核心冲突:试图理解海森堡1941年神秘访问的真实动机,同时反思科学伦理在战争中的边界。

玛格丽特·玻尔(Margrethe Bohr)

身份:尼尔斯·玻尔的妻子,敏锐的观察者和家庭情感的核心。性格与特质:

警觉与怀疑:对海森堡的敌意贯穿始终,质疑其在德国占领下的忠诚度(“他是德国人,我们是丹麦人”)。情感纽带:作为玻尔思想的倾听者与记录者,以局外人视角揭示对话的潜台词。历史见证者:通过回忆(如儿子克里斯蒂安的死亡)隐喻战争对个人与家庭的创伤。剧中核心冲突:在科学讨论与政治猜忌之间,成为道德与情感的“第三视角”,推动真相的探寻。

维尔纳·海森堡(Werner Heisenberg)

身份:德国物理学家,量子力学先驱,“不确定性原理”提出者。性格与特质:

天才与争议:科学上激进创新(如“量子力学”的突破),政治上因纳粹德国背景背负道德质疑。矛盾与自辩:坚称战时研究仅用于核能开发,却因未能明确拒绝武器化可能遭历史诟病(“我一生都在解释”)。孤独与挣扎:渴望玻尔的认可(“你是我精神的父亲”),又因立场的对立陷入永恒的误解。剧中核心冲突:试图向玻尔夫妇证明1941年访问的“善意”(传递德国核计划信息?寻求道德赦免?),却成为科学伦理的永恒谜题。

这是关于科学和道德的撕扯,三人对话重现了二战中科学家如何在国家忠诚、人性良知与学术理想间抉择。记忆的不可靠性:通过多重回忆视角(如“十月还是九月?”),暗示历史真相的模糊性与叙事的权力。量子隐喻:角色互动宛如“不确定性原理”的具象化——动机、语言与记忆的交叠构成无法观测的“叠加态”。

ACT ONE

Margrethe: But why?

Bohr: You’re still thinking about it?

Margrethe: Why did he come to Copenhagen?

Bohr: Does it matter, my love, now we’re all three of us dead and gone?

Margrethe: Some questions remain long after their owners have died. Lingering like ghosts. Looking for the answers they never found in life.

Bohr: Some questions have no answers to find.

Margrethe: Why did he come? What was he trying to tell you?

Bohr: He did explain later.

Margrethe: He explained over and over again. Each time he explained it became more obscure.

Bohr: It was probably very simple, when you come right down to it: he wanted to have a talk.

Margrethe: A talk? To the enemy? In the middle of a war?

Bohr: Margrethe, my love, we were scarcely the enemy.

Margrethe: It was 1941!

Bohr: Heisenberg was one of our oldest friends.

Margrethe: Heisenberg was German. We were Danes. We were under German occupation.

Bohr: It put us in a difficult position, certainly.

Margrethe: I’ve never seen you as angry with anyone as you were with Heisenberg that night.

Bohr: Not to disagree, but I believe I remained remarkably calm.

Margrethe: I know when you’re angry.

Bohr: It was as difficult for him as it was for us.

Margrethe: So why did he do it? Now no one can be hurt, now no one can be betrayed.

Bohr: I doubt if he ever really knew himself.

Margrethe: And he wasn’t a friend. Not after that visit. That was the end of the famous friendship between Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg.

Heisenberg: Now we’re all dead and gone, yes, and there are only two things the world remembers about me. One is the uncertainty principle, and the other is my mysterious visit to Niels Bohr in Copenhagen in 1941. Everyone understands uncertainty. Or thinks he does. No one understands my trip to Copenhagen. Time and time again I’ve explained it. To Bohr himself, and Margrethe. To interrogators and intelligence officers, to journalists and historians. The more I’ve explained, the deeper the uncertainty has become. Well, I shall be happy to make one more attempt. Now we’re all dead and gone. Now no one can be hurt, now no one can be betrayed.

Margrethe: I never entirely liked him, you know. Perhaps I can say that to you now.

Bohr: Yes, you did. When he was first here in the twenties? Of course you did. On the beach at Tisvilde with us and the boys? He was one of the family.

Margrethe: Something alien about him, even then.

Bohr: So quick and eager.

Margrethe: Too quick. Too eager.

Bohr: Those bright watchful eyes.

Margrethe: Too bright. Too watchful.

Bohr: Well, he was a very great physicist. I never changed my mind about that.

Margrethe: They were all good, all the people who came to Copenhagen to work with you. You had most of the great pioneers in atomic theory here at one time or another.

Bohr: And the more I look back on it, the more I think Heisenberg was the greatest of them all.

Heisenberg: So what was Bohr? He was the first of us all, the father of us all. Modern atomic physics began when Bohr realised that quantum theory applied to matter as well as to energy. 1913. Everything we did was based on that great insight of his.

Bohr: When you think that he first came here as my assistant in 1924…

Heisenberg: I’d only just finished my doctorate, and Bohr was the most famous atomic physicist in the world.

Bohr: … and in just over a year he’d invented quantum mechanics.

Margrethe: It came out of his work with you.

Bohr: Within three he’d got uncertainty.

Margrethe: And you’d done complementarily.

Bohr: We argued them both out together.

Heisenberg: We did most of our best work together.

Bohr: Heisenberg usually led the way.

Heisenberg: Bohr made sense of it all.

Bohr: We operated like a business.

Heisenberg: Chairman and managing director.

Margrethe: Father and son.

Heisenberg: A family business.

Margrethe: Even though we had sons of our own.

Bohr: And we went on working together long after he ceased to be my assistant.

Heisenberg: Long after I’d left Copenhagen in 1927 and gone back to Germany. Long after I had a chair and a family of my own.

Margrethe: Then the Nazis came to power…

Bohr: And it got more and more difficult. When the war broke out - impossible. Until that day in 1941.

Margrethe: When it finished forever.

Bohr: Yes, why did he do it?

Heisenberg: September, 1941. For years I had it down in my memory as October.

Margrethe: September. The end of September.

Bohr: A curious sort of diary memory is.

Heisenberg: You open the pages, and all the neat headings and tidy jottings dissolve around you.

Bohr: You step through the pages into the months and days themselves.

Margrethe: The past becomes the present inside your head.

Heisenberg: September, 1941, Copenhagen… And at once here I am, getting off the night train from Berlin with my colleague Carl von Weizsacker. Two plain civilian suits and raincoats among all the field.grey Wehrmacht uniforms arriving with us, all the naval gold braid, all the well-tailored black of the SS. In my bag I have the text of the lecture I’m giving. In my head is another communication that has to be delivered. The lecture is on astrophysics. The text inside my head is a more difficult one.

Bohr: We obviously can’t go to the lecture.

Margrethe: Not if he’s giving it at the German Cultural Institute - it’s a Nazi propaganda organisation.

Bohr: He must know what we feel about that.

Heisenberg: Weizsacker has been my John the Baptist. and written to warn Bohr of my arrival.

Margrethe: He wants to see you?

Bohr: I assume that’s why he’s come.

Heisenberg: But how can the actual meeting with Bohr be arranged?

Margrethe: He must have something remarkably important to say.

Heisenberg: It has to seem natural. It has to be private.

Margrethe: You’re not really thinking of inviting him to the house?

Bohr: That’s obviously what he’s hoping.

Margrethe: Niels! They’ve occupied our country!

Bohr: He is not they.

Margrethe: He’s one of them.

Heisenberg: First of all there’s an official visit to Bohr’s workplace, the Institute for Theoretical Physics, with an awkward lunch in the old familiar canteen. No chance to talk to Bohr, of course. Is he even present? There’s Rozental… Petersen, I think… Christian M?ller, almost certainly… It’s like being in a dream. You can never quite focus the precise details of the scene around you. At the head of the table .Is that Bohr? I turn to look, and it’s Bohr, it’s Rozental, it’s M?ller it’s whoever I appoint to be there… A difficult occasion, though I remember that clearly enough.

Bohr: It was a disaster. He made a very bad impression. Occupation of Denmark unfortunate. Occupation of Poland, however, perfectly acceptable. Germany now certain to win the war.

Heisenberg: Our tanks are almost at Moscow. What can stop us? Well, one thing, perhaps. One thing.

Bohr: He knows he’s being watched, of course. One must remember that. He has to be careful about what he says.

Margrethe: Or he won’t be allowed to travel abroad again.

Bohr: My love, the Gestapo planted microphones in his house. He told Goudsmit when he was in America. The SS brought him in for interrogation in the basement at the Prinz-Albert-Strasse.

Margrethe: And then they let him go again.

Heisenberg: I wonder if they suspect for one moment how painful it was to get permission for this trip. The humiliating appeals to the Party, the demeaning efforts to have strings pulled by our friends in the Foreign Office.

Margrethe: How did he seem? Is he greatly changed?

Bohr: A little older.

Margrethe: I still think of him as a boy.

Bohr: He’s nearly forty. A middle-aged professor, fast catching up with the rest of us.

Margrethe: You still want to invite him here?

Bohr: Let’s add up the arguments on either side in a reasonably scientific way. Firstly, Heisenberg is a friend…

Margrethe: Firstly, Heisenberg is a German.

Bohr: A White Jew. That’s what the Nazis called him. He taught so-called Jewish physics. And refused to stop. He stuck with Einstein and relativity, in spite of the most terrible attacks.

Margrethe: All the real Jews have lost their jobs. He’s still teaching.

Bohr: He’s still teaching relativity.

Margrethe: Still a professor at Leipzig.

Bohr: At Leipzig, yes. Not at Munich. They kept him out of the chair at Munich.

Margrethe: He could have been at Columbia.

Bohr: Or Chicago. He had offers from both.

Margrethe: He wouldn’t leave Germany.

Bohr: He wants to be there to rebuild German science when Hitler goes. He told Goudsmit.

Margrethe: And if he’s being watched it will all be reported upon. Who he sees. What he says to them. What they say to him.

Heisenberg: I carry my surveillance around like an infectious disease. But then I happen to know that Bohr is also under surveillance.

Margrethe: And you know you’re being watched yourself.

Bohr: By the Gestapo?

Heisenberg: Does he realise?

Bohr: I’ve nothing to hide.

Margrethe: By our fellow-Danes. It would be a terrible betrayal of all their trust in you if they thought you were collaborating.

Bohr: Inviting an old friend to dinner is hardly collaborating.

Margrethe: It might appear to be collaborating.

Bohr: Yes. He’s put us in a difficult position.

Margrethe: I shall never forgive him.

Bohr: He must have good reason. He must have very good reason.

Heisenberg: This is going to be a deeply awkward occasion.

Margrethe: You won’t talk about politics?

Bohr: We’ll stick to physics. I assume it’s physics he wants to talk to me about.

Margrethe: I think you must also assume that you and I aren’t the only people who hear what’s said in this house. If you want to speak privately you’d better go out in the open air.

Bohr: I shan’t want to speak privately.

Margrethe: You could go for another of your walks together.

Heisenberg: Shall I be able to suggest a walk?

Bohr: I don’t think we shall be going for any walks. Whatever he has to say he can say where everyone can hear it.

Margrethe: Some new idea he wants to try out on you, perhaps.

Bohr: What can it be, though? Where are we off to next?

Margrethe: So now of course your curiosity’s aroused…, in spite of everything.

Heisenberg: So now here I am, walking out through the autumn twilight to the Bohrs' house at Ny-Carlsberg. Followed, presumably, by my invisible shadow. What am I feeling? Fear, certainly - the touch of fear that one always feels for a teacher, for an employer, for a parent. Much worse fear about what I have to say. About how to express it. How to broach it in the first place. Worse fear still about what happens if I fail.

Margrethe: It’s not something to do with the war?

Bohr: Heisenberg is a theoretical physicist. I don’t think anyone has yet discovered a way you can use theoretical physics to kill people.

Margrethe: It couldn’t be something about fission?

Bohr: Fission? Why would he want to talk to me about fission?

Margrethe: Because you’re working on it.

Bohr: Heisenberg isn’t.

Margrethe: Isn’t he? Everybody else in the world seems to be. And you’re the acknowledged authority.

Bohr: He hasn’t published on fission.

Margrethe: It was Heisenberg who did all the original work on the physics of the nucleus. And he consulted you then, he consulted you at every step.

Bohr: That was back in 1932. Fission’s only been around for the last three years.

Margrethe: But if the Germans were developing some kind of weapon based on nuclear fission…

Bohr: My love, no one is going to develop a weapon based on nuclear fission.

Margrethe: But if the Germans were trying to, Heisenberg would be involved.

Bohr: There’s no shortage of good German physicists.

Margrethe: There’s no shortage of good German physicists in America or Britain.

Bohr: The Jews have gone, obviously.

Heisenberg: Einstein, Wolfgang Pauli, Max Born… Otto Frisch, Lise Meitner… We led the world in theoretical physics! Once.

Margrethe: So who is there still working in Germany?

Bohr: Sommerfeld, of course. Von Laue.

Margrethe: Old men.

Bohr: Wirtz. Harteck.

Margrethe: Heisenberg is head and shoulders above all of them.

Bohr: Otto Hahn - he's still there. He discovered fission, after all.

Margrethe: Hahn's a chemist. I thought that what Hahn discovered…

Bohr: …was that Enrico Fermi had discovered it in Rome four years earlier. Yes - he just didn’t realize it was fission. It didn’t occur to anyone that the uranium atom might have split, and turned into two atoms of barium. Not until Hahn and Strassmann did the analysis, and detected the barium.

Margrethe: Fermi's in Chicago.

Bohr: His wife’s Jewish.

Margrethe: So Heisenberg would be in charge of the work?

Bohr: Margrethe, there is no work! John Wheeler and I did it all in 1939. One of the implications of our paper is that there’s no way in the foreseeable future in which fission can be used to produce any kind of weapon.

Margrethe: Then why is everyone still working on it?

Bohr: Because there’s an element of magic in it. You fire a neutron at the nucleus of a uranium atom and it splits into two atoms of barium. It’s what the alchemists were trying to do - to turn one element into another.

Margrethe: So why is he coming?

Bohr: Now your curiosity’s aroused.

Margrethe: My forebodings.

Heisenberg: I crunch over the familiar gravel to the Bohrs' front door, and tug at the familiar bell-pull. Fear, yes. And another sensation, that's become painfully familiar over the past year. A mixture of self-importance and sheer helpless absurdity - that of all the 2,000 million people in this world, I'm the one who's been charged with this impossible responsibility… The heavy door swings open.

Bohr: My dear Heisenberg!

Heisenberg: My dear Bohr!

Bohr: Come in, come in…

Margrethe: And of course as soon as they catch sight of each other, all their caution disappears. The old flames leap up from the ashes. If we can just negotiate all the treacherous little opening civilities…

Heisenberg: I'm so touched you felt able to ask me.

Bohr: We must try to go on behaving like human beings.

Heisenberg: I realise how awkward it is.

Bohr: We scarcely had a chance to do more than shake hands at lunch the other day.

Heisenberg: And Margrethe, I haven't seen…

Bohr: Since you were here four years ago.

Margrethe: Niels is right. You look older.

Heisenberg: I had been hoping to see you both in 1938, at the congress in Warsaw…

Bohr: I believe you had some personal trouble.